The Glorious mysteries are one of the three traditional sets of events of the life of Christ and the Blessed Virgin Mary. Pope Leo XIII said of the Glorious Mysteries that they reveal the mediation of the great Virgin, still more abundant in fruitfulness. She rejoices in heart over the glory of her Son triumphant over death, and follows Him with a mother's love in His Ascension to His eternal kingdom; but, though worthy of Heaven, she abides a while on earth, so that the infant Church may be directed and comforted by her "who penetrated, beyond all belief, into the deep secrets of Divine wisdom" (St. Bernard). The first three meditations are taken from scripture. The Resurrection of our Lord, His Ascension into heaven and the Descent of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost are all meditations on scriptural events. The fourth meditation (the Assumption of Mary) and fifth meditation (Coronation of Mary as Queen of Heaven) are part of Catholic devotion, and contemplate beauty and hope in the human condition.

Wednesday, July 30, 2014

Sunday, July 27, 2014

Fifth Sorrowful Mystery: The Crucifixion of Our Lord

That we Catholics so frequently see crucifixes in our homes and churches might, in a certain way, desensitize us to the horrors that it represents in a relatively sanitised form. The crucifix—which we proudly wear as a symbol of our faith and a sign of hope—is a remembrance of a gruesome and barbaric act of inhumanity, a depiction of the gravest historical injustice imaginable (simultaneously the cruel murder of a totally innocent man, perpetrated for personal expedience but enacted in the name of a fake justice, and the desecration of God’s only begotten).

Yet it is in this moment—the moment when Jesus looks most unlike God, most reducible to that which is rejected by humans—that the depths of divine love are revealed: in the veiling of his death, Christ’s true identity as God's own way of reaching out and loving humanity is revealed. God wills, in the mystery of Christ’s suffering, death and resurrection, to love us into new communion with Himself, thereby bestowing new meaning on human suffering itself. This man of sorrows was never without the joy of the beatific vision.

Through the eyes of faith, then, we see Christ’s own perfect self-offering as priest and victim, a true and proper sacrifice offered for our ransom and reconciliation, atoning for our sins and meriting all the graces that we receive and could ever receive. The eyes of faith allow us to see already, here at Calvary, the glorious conclusion of Christ’s work of redemption in the resurrection and ascension: this authentically human death in obedience to the Father merits the rewards of exaltation from God, firstly for Himself and (God-willing) for we who appropriate it in our own lives.

In times of sorrow, it can be difficult to sense God's presence: suffering seems meaningless and it is as if the ink of God's handwriting is invisible against the darkness of life's paper. Yet, as we endure the sorrows and mini-'crucifixions' that come in our own lives, may Mary's prayers helps us to unite our sorrows to Christ's death, so that we may experience a foretaste of the joy of our own resurrection, and come to see God's handwriting by the light shed from the empty tomb.

Friday, July 25, 2014

Book review: Green Philosophy by Roger Scruton

There have always been different perspectives on how we interact with animals and the environment. Saint Francis loved birds landing on his arm, with animals beside him as he contemplated brother sun and sister moon. On the other hand, according to Blessed Cecilia, Saint Dominic when preaching to nuns from behind a grille in their convent, plucked the feathers from a sparrow that had flown into the church, shouting that it was the devil that had came to interrupt his sermon!

Someone with an alternative perspective on the environment is Professor Roger Scruton, a fellow of Blackfriars Hall. In his book Green Philosophy, Prof. Scruton calls for a greater focus on how non-political grassroots and voluntary organisations can address both local and global scale environmental issues. His main premise is that a top-down, government-directed approach is never going to fully address global problems like climate change. Scruton has grave concerns that such an approach is counter-productive and only serves to take power away from individuals, bankrupt small businesses and favour those with an interest in gaining a competitive advantage with new legislation being introduced. Scruton is particularly critical of the European Union and the seemingly endless number of regulations aimed at protection of the environment. His philosophy is that such top-down directives become a burdensome array of counter-productive legislation at both a local and national level.

Scruton gives examples where various systems of top-down government have caused massive damage to the environment. The ‘tragedy of the commons’ happens when everyone has access to unowned or commonly owned resources (such as fish in a lake, the air we breathe). Such resources are easily depleted by our use of them, particularly if there is a situation where it is in the interest of individuals to take as much as they can before others deprive them of the chance. Natural resources or ecosystems become someone else’s problem. When there is no accountability for stewardship of a common resource, the result is usually environmental degradation.

The evidence is certainly there to prove his point on the issue of climate change. Global CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere are at the highest levels ever recorded and show no signs of stabilising. Deforestation continues across the world. Despite all the attempts at gaining a global agreement on climate change, the problem of increasing carbon emissions and decreasing capacity of the planet’s ability to cope is only getting worse. Scruton sees some climate change activists as being less interested in society adapting to climate change, and more interested in perpetuating a system of government which provides them with a cushy job role. Scruton also criticises the approach of many unaccountable non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in their blatant bypassing of the democratic system through lobbying Government or even donating to political parties.

Overall, Scruton proposes that we should switch from a fast-paced, fossil-fuel intensive living, to a local way of life focused on organic agriculture, farmers’ markets, locally-sourced food, more local holidays and so on. Scruton suggests we abandon the impossible task of getting all nations to implement treaties on carbon trading and limiting greenhouse gas emissions. Instead, he proposes that we should invest in developing clean technology, and agreeing on treaties that can actually be globally implemented. He also suggests we radically reform (or indeed get rid of) the system of agricultural subsidies which generally favour corporations and resource-intensive monoculture farming. In other words, taxes should be funding the technological advancements and local-scale innovation that is needed to deal with climate change in the 21st century, rather than more bureaucracy on carbon emissions. Prof Scruton outlines a philosophical term ‘oikophilia’ or love of home, as the primary motivation for care of the earth. Scruton believes oikophilia can be promoted with a shift away from government-shaped solutions and instead sees non-political ‘grassroots’ organisations like the National Trust, Womens Institute, RSPB, and so on as the ones which should be protecting the environment.

Prof Scruton’s proposals are not a silver bullet to environmental concerns, nor does he claim to have one. Of course, not everyone is able to commit to supporting a grassroots organisation, or has the income to buy locally-grown food from independent stores. However, Scruton does put forward a theory that oikophilia is degraded by modern pursuits such as home entertainment, television, and other activities which instead of building up virtue in our lives, leave us empty. In traditional moralising language, vice and sin are what degrades oikophilia, with greed driving a consumerism that is ultimately unsustainable.

In our Dominican tradition, I should recognise the truth contained in Green Philosophy and applaud Scruton for the very useful criticisms of the government-led approach. However, Scruton’s deregulated and small government framework for ‘green conservatism’ seems to neglect the positive achievements on certain environmental issues through a ‘top-down’ approach. For instance, EU regulations on vehicle emission standards is reducing toxic air pollution from vehicles in European towns and cities. This was done by forcing car manufacturers to increase engine efficiency and improve pollution control. The EU is also requiring energy companies to use less polluting fuels and use more renewable sources of power. The top-down directive approach has revolutionised how we view waste as a resource in this country, with the EU setting waste targets and offering best practice on new waste treatment technology. Government grants are supposed to be available for businesses and organisations to access, in order to deal with the anomalies that occur in this top-down approach.

As for green conservatism, placing an emphasis on tradition in architecture, and starting up permaculture projects are good things. However, I cannot see how small government and a volunteer based approach would work in some cases. It is hard to see the Womens Institute coming together to remedy the problem of contaminated land from the old gasworks in the nearby industrial estate. Or the National Trust appearing with volunteers to clean up Sellafield, with their membership passes in the pockets of their radiation suits. Although Scruton points out failures in certain top-down legislation on habitats and protected species, the general trend is that things have improved greatly over the last 40 years in terms of protection of the environment. European legislation and international treaties have delivered positive results on protection of endangered species. Accession countries such as Poland who are new members of the EU, are being forced to clean up their industries, deal with major pollution problems and protect sites of ecological importance. The collaborative international approach with some degree of top-down government directive has been successful in meeting environmental objectives.

Waste not: EU directives have revolutionised how we manage waste as a resource

As for green conservatism, placing an emphasis on tradition in architecture, and starting up permaculture projects are good things. However, I cannot see how small government and a volunteer based approach would work in some cases. It is hard to see the Womens Institute coming together to remedy the problem of contaminated land from the old gasworks in the nearby industrial estate. Or the National Trust appearing with volunteers to clean up Sellafield, with their membership passes in the pockets of their radiation suits. Although Scruton points out failures in certain top-down legislation on habitats and protected species, the general trend is that things have improved greatly over the last 40 years in terms of protection of the environment. European legislation and international treaties have delivered positive results on protection of endangered species. Accession countries such as Poland who are new members of the EU, are being forced to clean up their industries, deal with major pollution problems and protect sites of ecological importance. The collaborative international approach with some degree of top-down government directive has been successful in meeting environmental objectives.

As for the skeptics who do not believe climate change is something to be concerned about, Scruton helpfully recommends reading Global Warming: The Complete Briefing by Sir John Houghton, which is a balanced and comprehensive overview. He also cites Sustainable Energy without the Hot air by David JC MacKay as a good source of further information on energy related issues. I do agree with Prof. Scruton that non-political and accountable local associations, and indeed local churches will, at the end of the day, achieve more than any attempt at having a global carbon trading ‘market’ or the futile attempts at trying to get another Kyoto agreement on greenhouse gases. Going to Church to pray will likely have more of a positive overall impact than either of these.

Scruton makes an interesting point that we must recognise the difference between a religion directed towards salvation (which tends to ignore the environment), and a religion focused on the immediate presence of the sacred, as this is revealed in the here and now. The two may of course be combined, but are clearly different as motives. A care for sacred places is an obstacle to destruction of the environment, and Scruton’s argument is that care for sacred places is part of the domestication of religion. This means attaching the Christian faith to local saints, shrines, towns and civic ceremonies, even the law of a nation. This personalising of our connection to the environment is of course lost through rampant consumerism and the extremes of individualism.

In the meantime, our sacristy in Blackfriars has an infestation of flies which will be duly sprayed with chemicals so we can get on with our preaching.

In the meantime, our sacristy in Blackfriars has an infestation of flies which will be duly sprayed with chemicals so we can get on with our preaching.

Thursday, July 24, 2014

Fourth Sorrowful Mystery: The Carrying of the Cross

|

| Titian, Christ Carrying the Cross (c.1565) |

When we pray the Fourth Sorrowful Mystery we bring to mind our Lord's anguish and pain as he carried the weight of our sins on the cross, knowing the greater sacrifice that awaited him on the summit of Calvary.

Recalling our Lord's act leaves us feeling humbled, contrite but encouraged by his overwhelming love for us, His children. Our cross is light to bear, by comparison with Christ's inestimable sacrifice.

A good intention, therefore, when praying this mystery is to pray for those who are without hope, and feel overburdened. That they may take up their cross and follow Him, for it is only in carrying our cross with love, in faith, and for the hope of the life to come that we find happiness.

– Br Samuel Burke OP

Could you sponsor the Friars to help train new priests?

Today, four Dominican Friars will take the first steps on a 190-mile trek across England. This is a final plea for sponsors – many men are currently joining our Order, and we urgently need to raise money to fill a gap we have in our funds for training them.

So far we have reached 76% of our sponsorship target - £15,196 out of £20,000. Could you help us get closer to our goal?

https://www.justgiving.com/teams/TheFriars

http://www.catholicherald.co.uk/news/2014/06/06/order-asks-for-1m-to-fund-rise-in-vocations/

So far we have reached 76% of our sponsorship target - £15,196 out of £20,000. Could you help us get closer to our goal?

https://www.justgiving.com/teams/TheFriars

http://www.catholicherald.co.uk/news/2014/06/06/order-asks-for-1m-to-fund-rise-in-vocations/

Monday, July 21, 2014

Third Sorrowful Mystery: The Crowning with Thorns

|

| Mantegna, 'Ecce homo' (1500) |

Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do. (Luke 23:34)

These words of Jesus hanging on the Cross reveal a profound truth about the present scene of his crowning with thorns. What must have pained our Lord above all is the knowledge that his own people, these sons and daughters of God, were tormenting him to death without knowing his true identity or the depth of his love for them. The worst pains we suffer are inflicted by those we love.

All the Sorrowful Mysteries invite us to weep for Jesus, in his terrible sufferings, but also to weep with Jesus. As the unruly crowd calls for his blood and looks on at this scourged and bleeding man – Ecce homo! Behold the man! – our Lord is silently looking back at them and loving them. He is grieving not for his own pains, but for the sins of his beloved people who have turned against him.

So it is not just the sheer cruelty that makes me want to recoil from this scene. It is also the dramatic, even tragic, irony of it all. The Roman soldiers are mocking Christ and, specifically, his claim to kingship. They have wrapped him in a robe of royalty, put a pathetic stick of authority in his hand, and a twisted crown of thorns on his head. I wince at the thought of those thorns – superfluous, barbaric cruelty. And this cruelty exacerbates the fact that the mockery is totally unjustified: for Christ is just, Christ is innocent, and Christ is king. He is true man – 'a man of sufferings and acquainted with grief' – and also true God, the God who looks upon us with infinite love despite our sins.

It is good to pray this mystery for all those in authority, for those suffering persecution or torture, and for those who do not recognise Christ as king.

Thursday, July 17, 2014

Assisted Dying: Love vs autonomy

|

| The Good Samaritan |

In a previous post I discussed some of the issues with the proposed “Assisted Dying” legislation from a procedural perspective in a Parliamentary democracy. In today’s post I want to give some consideration to the values which underpin our society and what the implementation of the proposed legislation would mean for them.

Now depending on who you speak to, the United Kingdom is a Christian society or used to be one. However, regardless of where they stand on this issue, few would argue that many of our most cherished institutions and many of our accepted moral norms have their root in Christianity, even if some believe that they are now divorced and independent from it.

Take, for example, the NHS; it’s not hard to see how an institution like this arises out of Jesus’s commandment to “Love thy neighbour”. Similarly, the welfare state is another example of society collectively living out the Parable of the Good Samaritan: we do not wish anybody to be left by the side of the street destitute, simply because they do not have a job or money. Whilst there are arguments of scale and scope, I have never actually met anyone in this country who would wish to get rid of welfare or the NHS. Such institutions send a message that everyone, irrespective of who they are now, or what they have done in their past, merits a certain level of respect and care; derived from their basic dignity as a human being.

At a more local level, there are tens of thousands of different groups, organisations, and individuals working up and down the country to improve the lives of others; and not because they are being forced to, but because they wish to help and care for others. This, too, is “Love they neighbour” in action.

Furthermore, implicit in all these good works at every level of society is an acknowledgment that loving can mean putting the interests of others before our own immediate interests. When you pay National Insurance and do not resist doing so, you are willingly receiving less of your salary than would otherwise be the case, so that others may benefit from the fruits of your labours. This is noble.

Thus it would not, I think, be an exaggeration to say that love of neighbour underpins many of the ways we seek to behave in this country. Furthermore, I suspect if many were asked what their ultimate moral value was they might reply with the Golden Rule, “Do as you would be done by”. We remain a loving society and one which respects acts of kindness to others. You only have to observe how feel-good YouTube videos showing kindness in unexpected places go viral.

What then is the ultimate value which underlies the campaign behind the “Assisted Dying” campaign? Is it to make us more loving? No, ultimately it is about autonomy. There are other values mixed in there, and that people may cite: care and compassion, love and the desire not to see another suffer (and I don’t doubt the sincerity and good of them); but whilst "assisted dying" remains a voluntary decision, then the ultimate value remains autonomy. The proponents of the legislation are not saying that somebody with a limited amount of time to live and certain level of suffering shouldrequest help to commit suicide, but rather they want a situation where that person could request the necessary help. Thus the choice of individual is the heart of the argument, and autonomy is key.

In fact in many areas of life at the moment there is increasing propensity to talk in terms of autonomy, generally at the expense of absolute values. Autonomy itself becomes the absolute value. There is a creeping trend to define us as beings that choose, not as beings that seek to choose well. Autonomy, not love, is at the heart of the sexual revolution; autonomy, not love, is at the heart of the pro-choice campaign; autonomy, not love, is at the heart of the liberalisation of pornography; and autonomy, not love, is at the heart of the current campaign.

|

| Choice is not in and of itself a good thing |

Choice is not a good in and of itself. Its good is dependent on there being a good choice for us to make. The choice between being able to become addicted to heroin or crack-cocaine is not a good. The choice between mutilating my left side or my right side is not a good. The introduction of a choice so that we can now assist somebody to kill themselves with the backing of the law is not a good. It is a choice we would be better without.

The obvious riposte to this is that I do not have to live with terminal illness, with pain and suffering, and with the fear of it getting ever-worse. This is true, and I have great sympathy for someone who wishes to take their own life and feels there is no other option, but I cannot condone them in this choice and always find suicide tragic. My reaction to cases of suicide is to think about what we could have done to make that person feel that taking their own life was not their best option. And the fact is that palliative care is far more effective than many realise and is improving all the time. And it is also as the law currently stands a responsibility on us to fund adequately and to make sure it is available to all who need it. However, should the “Assisted Dying” Bill pass into statute, it will absolve us of this responsibility. Where appropriate palliative care is deemed too onerous or too expensive, we will be able to respond to the patient, “Ah, well you do have a choice you know, you don’t have to suffer like this.” In short, the triumph of autonomy will excuse us from being more loving, from valuing someone, even when they don’t value themselves.

There is also an inherent problem with choice; for it is incumbent upon us to consider whether we should choose one option or another. “I choose death” is not a response which we should be building into our legal framework. Patients should be able to focus on living well. That does not mean prolonging life just for the sake of it, but rather that everything should be done to be make life as good as possible whilst we still have the gift of it. Similarly families and doctors should be single-minded in their provision of love and comfort, not working and caring with the alternative of helping the patient to kill themselves if it all becomes too much. It's hard to fully commit to the sometimes onerous task of loving fully, when the spectre of an easier way out is in the background. Such a choice not only undermines love and trust between patient and carer, but also puts doctors in the invidious position of having to help kill people, not what they will have joined the medical profession to do. What would it to the emotional well-being of a doctor to make them an agent of death?

There is still the riposte from those in favour of the legislation that the choice is only for those who want it and that is exactly what the issue of autonomy is all about. However, this is just naive. As John Donne astutely observed in his poignant meditations, “No man is an Island”. Every human action affects the rest of humanity in some way. Patterns of behaviour create expectations of behaviour. “Alice chose not to be a burden, are you sure you want to carry on, what with so much pain and everything?” . . . “Obviously, we don’t want you to die, BUT have you thought about. . . ?” One person’s struggle for autonomy forces a choice on many who just want to live the term of their natural life. Uncomfortable as it feels to say it, even in extreme suffering we have a responsibility to think about how our actions impinge upon others. There are disabled and terminally ill people already scared by the pressure that they feel will inevitably be place upon them to take their lives, and saying "don't worry, it's your choice" is not going to reassure them.

For an eloquent account of the very real fear of the pressure to choose to die and the way that the doctor-patient relationship is affected I would recommend Penny Pepper’s moving article http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/jul/16/disabled-help-to-live-not-die-lord-falconer-assisted-dying-bill. She has the following to say:

I tried to commit suicide when I was 19. How tragic, you might say, so young and so unhappy. Yet if I tell you I’ve had a chronic illness since early childhood that is known for excruciating pain, for causing immobility and secondary – sometimes life-threatening – conditions, does that change your view of my suicide attempt?

I was unhappy and badly needed mental health support to treat depression. Sad to say that the standard response was to link my illness and disability automatically to my depression – and my “understandable” suicide attempt. There is a link, but not the one perceived by mainstream thought, medical or otherwise. I was stuck in an isolated dead-end existence within the family home, and as I wrote in the Guardian recently my mother was my only carer.

It felt like there was no chance of escape from a pointless existence; frustration dragged my depression into a downward spiral and I attempted suicide. I was in despair with barriers, with limits on personal freedom, and lack of independence – issues that can be alleviated by proper social care and the adaptation of physical boundaries.

Pain was, and is, a constant. But for the rest of my life I want to experience, to feel and to create as much as I can. I believe I am as valuable, with all my flaws and contradictions, as any other average human being. Yet the bill to legalise assisted dying – to be debated in the Lords on Friday – puts us on a dangerous road of devaluing disabled people. It frightens many; it frightens me.

The final point I want to make is that for all the talk about autonomy there is another more pernicious under-current behind the proposed legislation. It is simply that some lives are worth less than others. Penny Pepper alludes to this above with reference to depression and disability. People with severe disabilities and terminal illness are to be considered less worthy of the full spectrum of medical treatment than those it is considered have “something to live for.” If this were not the case, then why would the “Assisted Dying” Bill restrict its remit to the provision of assistance with suicide to those who are terminally ill. Why should anybody who wishes to kill themselves not have their autonomy respected? Surely this can only be because the life of the terminally ill is less respected.

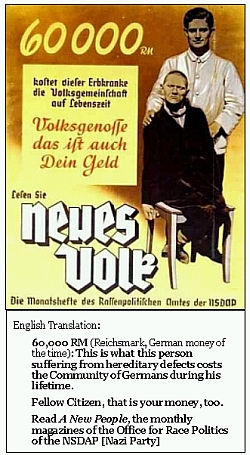

|

| Euthanasia Propoganda Poster |

Evidence of this dangerous type of thinking is evidenced by many of those who argue for the Bill. It is sad to see that it has crept into the thinking of the former Archbishop of Canterbury, Lord Carey, formerly a staunch defender of the current legal position. Notice that in saying how his mind was changed, he cites the case of Tony Nicklinson – a man who was not terminally ill and would not have been assisted by the proposed legislation. Tony Nicklinson was severely disabled, but this neatly illustrates the way that even thinking about this sort of legislation gets us into the mindset of apportioning different value to different lives according to their different physical states. Surely the tragedies of the last century are not fading from our memories so fast that we think this is anything other than an abhorrent way to think? Do we really want to live in a society where on encountering the man on Beachy Head we attempt to talk him out of jumping, but on finding out that he has terminal cancer, we agree to give him a helpful shove?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)