|

| The Good Samaritan |

In a previous post I discussed some of the issues with the proposed “Assisted Dying” legislation from a procedural perspective in a Parliamentary democracy. In today’s post I want to give some consideration to the values which underpin our society and what the implementation of the proposed legislation would mean for them.

Now depending on who you speak to, the United Kingdom is a Christian society or used to be one. However, regardless of where they stand on this issue, few would argue that many of our most cherished institutions and many of our accepted moral norms have their root in Christianity, even if some believe that they are now divorced and independent from it.

Take, for example, the NHS; it’s not hard to see how an institution like this arises out of Jesus’s commandment to “Love thy neighbour”. Similarly, the welfare state is another example of society collectively living out the Parable of the Good Samaritan: we do not wish anybody to be left by the side of the street destitute, simply because they do not have a job or money. Whilst there are arguments of scale and scope, I have never actually met anyone in this country who would wish to get rid of welfare or the NHS. Such institutions send a message that everyone, irrespective of who they are now, or what they have done in their past, merits a certain level of respect and care; derived from their basic dignity as a human being.

At a more local level, there are tens of thousands of different groups, organisations, and individuals working up and down the country to improve the lives of others; and not because they are being forced to, but because they wish to help and care for others. This, too, is “Love they neighbour” in action.

Furthermore, implicit in all these good works at every level of society is an acknowledgment that loving can mean putting the interests of others before our own immediate interests. When you pay National Insurance and do not resist doing so, you are willingly receiving less of your salary than would otherwise be the case, so that others may benefit from the fruits of your labours. This is noble.

Thus it would not, I think, be an exaggeration to say that love of neighbour underpins many of the ways we seek to behave in this country. Furthermore, I suspect if many were asked what their ultimate moral value was they might reply with the Golden Rule, “Do as you would be done by”. We remain a loving society and one which respects acts of kindness to others. You only have to observe how feel-good YouTube videos showing kindness in unexpected places go viral.

What then is the ultimate value which underlies the campaign behind the “Assisted Dying” campaign? Is it to make us more loving? No, ultimately it is about autonomy. There are other values mixed in there, and that people may cite: care and compassion, love and the desire not to see another suffer (and I don’t doubt the sincerity and good of them); but whilst "assisted dying" remains a voluntary decision, then the ultimate value remains autonomy. The proponents of the legislation are not saying that somebody with a limited amount of time to live and certain level of suffering shouldrequest help to commit suicide, but rather they want a situation where that person could request the necessary help. Thus the choice of individual is the heart of the argument, and autonomy is key.

In fact in many areas of life at the moment there is increasing propensity to talk in terms of autonomy, generally at the expense of absolute values. Autonomy itself becomes the absolute value. There is a creeping trend to define us as beings that choose, not as beings that seek to choose well. Autonomy, not love, is at the heart of the sexual revolution; autonomy, not love, is at the heart of the pro-choice campaign; autonomy, not love, is at the heart of the liberalisation of pornography; and autonomy, not love, is at the heart of the current campaign.

|

| Choice is not in and of itself a good thing |

Choice is not a good in and of itself. Its good is dependent on there being a good choice for us to make. The choice between being able to become addicted to heroin or crack-cocaine is not a good. The choice between mutilating my left side or my right side is not a good. The introduction of a choice so that we can now assist somebody to kill themselves with the backing of the law is not a good. It is a choice we would be better without.

The obvious riposte to this is that I do not have to live with terminal illness, with pain and suffering, and with the fear of it getting ever-worse. This is true, and I have great sympathy for someone who wishes to take their own life and feels there is no other option, but I cannot condone them in this choice and always find suicide tragic. My reaction to cases of suicide is to think about what we could have done to make that person feel that taking their own life was not their best option. And the fact is that palliative care is far more effective than many realise and is improving all the time. And it is also as the law currently stands a responsibility on us to fund adequately and to make sure it is available to all who need it. However, should the “Assisted Dying” Bill pass into statute, it will absolve us of this responsibility. Where appropriate palliative care is deemed too onerous or too expensive, we will be able to respond to the patient, “Ah, well you do have a choice you know, you don’t have to suffer like this.” In short, the triumph of autonomy will excuse us from being more loving, from valuing someone, even when they don’t value themselves.

There is also an inherent problem with choice; for it is incumbent upon us to consider whether we should choose one option or another. “I choose death” is not a response which we should be building into our legal framework. Patients should be able to focus on living well. That does not mean prolonging life just for the sake of it, but rather that everything should be done to be make life as good as possible whilst we still have the gift of it. Similarly families and doctors should be single-minded in their provision of love and comfort, not working and caring with the alternative of helping the patient to kill themselves if it all becomes too much. It's hard to fully commit to the sometimes onerous task of loving fully, when the spectre of an easier way out is in the background. Such a choice not only undermines love and trust between patient and carer, but also puts doctors in the invidious position of having to help kill people, not what they will have joined the medical profession to do. What would it to the emotional well-being of a doctor to make them an agent of death?

There is still the riposte from those in favour of the legislation that the choice is only for those who want it and that is exactly what the issue of autonomy is all about. However, this is just naive. As John Donne astutely observed in his poignant meditations, “No man is an Island”. Every human action affects the rest of humanity in some way. Patterns of behaviour create expectations of behaviour. “Alice chose not to be a burden, are you sure you want to carry on, what with so much pain and everything?” . . . “Obviously, we don’t want you to die, BUT have you thought about. . . ?” One person’s struggle for autonomy forces a choice on many who just want to live the term of their natural life. Uncomfortable as it feels to say it, even in extreme suffering we have a responsibility to think about how our actions impinge upon others. There are disabled and terminally ill people already scared by the pressure that they feel will inevitably be place upon them to take their lives, and saying "don't worry, it's your choice" is not going to reassure them.

For an eloquent account of the very real fear of the pressure to choose to die and the way that the doctor-patient relationship is affected I would recommend Penny Pepper’s moving article http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/jul/16/disabled-help-to-live-not-die-lord-falconer-assisted-dying-bill. She has the following to say:

I tried to commit suicide when I was 19. How tragic, you might say, so young and so unhappy. Yet if I tell you I’ve had a chronic illness since early childhood that is known for excruciating pain, for causing immobility and secondary – sometimes life-threatening – conditions, does that change your view of my suicide attempt?

I was unhappy and badly needed mental health support to treat depression. Sad to say that the standard response was to link my illness and disability automatically to my depression – and my “understandable” suicide attempt. There is a link, but not the one perceived by mainstream thought, medical or otherwise. I was stuck in an isolated dead-end existence within the family home, and as I wrote in the Guardian recently my mother was my only carer.

It felt like there was no chance of escape from a pointless existence; frustration dragged my depression into a downward spiral and I attempted suicide. I was in despair with barriers, with limits on personal freedom, and lack of independence – issues that can be alleviated by proper social care and the adaptation of physical boundaries.

Pain was, and is, a constant. But for the rest of my life I want to experience, to feel and to create as much as I can. I believe I am as valuable, with all my flaws and contradictions, as any other average human being. Yet the bill to legalise assisted dying – to be debated in the Lords on Friday – puts us on a dangerous road of devaluing disabled people. It frightens many; it frightens me.

The final point I want to make is that for all the talk about autonomy there is another more pernicious under-current behind the proposed legislation. It is simply that some lives are worth less than others. Penny Pepper alludes to this above with reference to depression and disability. People with severe disabilities and terminal illness are to be considered less worthy of the full spectrum of medical treatment than those it is considered have “something to live for.” If this were not the case, then why would the “Assisted Dying” Bill restrict its remit to the provision of assistance with suicide to those who are terminally ill. Why should anybody who wishes to kill themselves not have their autonomy respected? Surely this can only be because the life of the terminally ill is less respected.

|

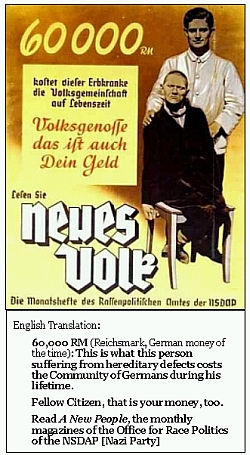

| Euthanasia Propoganda Poster |

Evidence of this dangerous type of thinking is evidenced by many of those who argue for the Bill. It is sad to see that it has crept into the thinking of the former Archbishop of Canterbury, Lord Carey, formerly a staunch defender of the current legal position. Notice that in saying how his mind was changed, he cites the case of Tony Nicklinson – a man who was not terminally ill and would not have been assisted by the proposed legislation. Tony Nicklinson was severely disabled, but this neatly illustrates the way that even thinking about this sort of legislation gets us into the mindset of apportioning different value to different lives according to their different physical states. Surely the tragedies of the last century are not fading from our memories so fast that we think this is anything other than an abhorrent way to think? Do we really want to live in a society where on encountering the man on Beachy Head we attempt to talk him out of jumping, but on finding out that he has terminal cancer, we agree to give him a helpful shove?

No comments:

Post a Comment