A fundamental tenet of Jesus’ preaching, and its urgency, was the proclamation of the imminent coming of the Kingdom of God. The parables of Jesus are a challenge to make a radical choice; to give up everything else “for the sake of the Kingdom of God”; while his miracles, linked to this preaching, are signs of the Messiah, of the foretold King anointed with the power of God: “But if it is by the Spirit of God that I cast out demons, then the kingdom of God has come to you” (Mt 12:28).

In giving an assertion of God’s rule over his creation, Scripture frequently employs images of God as ruler, as analogous to the most powerful humans in these ancient cultures. Proclamation of the kingdom of God, building on the tradition of YHWH’s rule over all creation, is fundamental to Jesus’ mission as depicted in the Gospels. The kingdom is not a geographical place; rather, it is a relationship of power, in which God and creature are properly aligned. That Jesus participates in God’s rule over creation as a result of his resurrection is the corollary of his “exaltation, glorification, ascension, and enthronement” at God’s right hand “The Lord says to my lord ‘Sit at my right hand until I make your enemies your footstool’” (Ps 110.1).

That his kingdom is eternal would seem to follow logically from the fact that the kingdom is God’s own rule over creation, which Jesus assumes because of his enthronement (Ps 110:1), and which is by definition eternal. The creed is specific here because of a concern raised by St Paul in his first letter to the church in Corinth (1 Cor 15:20-28). There, Paul is responding to those who deny the resurrection of the dead (15:12). He wants therefore to emphasise two things – first, they cannot yet be ruling, because the kingdom of God is not yet completely established, so sin and death are still ‘powers and authorities’

that must be conquered (1 Cor 15: 53-56). They are living only at the first stage, that of Christ’s being raised, but the second stage, which is coming, has not yet occurred. Hence, there was no evidence then – or now - for a bodily resurrection apart from Christ’s – this hasn’t yet happened to anyone else (although Mary's assumption body and soul into heaven is a unique participation in the new life Christ has won for us). Later, grappling with the Arian controversy, the pro-Nicene theologians were concerned lest this complex passage from Paul be read in a way that so emphasised the Son’s subordination to the Father that he might seem to be only a creature. Thus, they emphasise in the creed that his kingdom shall have no end.

This, too, is the crux of our contemporary problem – how can the kingdom be professed to have no end when it doesn’t seem to have begun? While the kingdom was “definitively established through [the events of] Christ’s cross” (Catechism §560), we are still caught between the already and the not yet, the continuing reign of injustice and sin in the world and the apparent absence, indifference or impotence of God in the face of all this. Yet we pray each day ‘thy kingdom come’; and we perhaps need to re-engage with the insight of Lumen Gentium (Vatican II) that we are presently pilgrims, travelling in the hope of arrival, where we will find the fulfilment of the kingdom in union with Christ. Such a profession, here as elsewhere, isn’t to be disparaged as deluded, wishful thinking, but seen rather as a challenge to enact what it says, seen also as a witness of our failure to live by God’s rule.

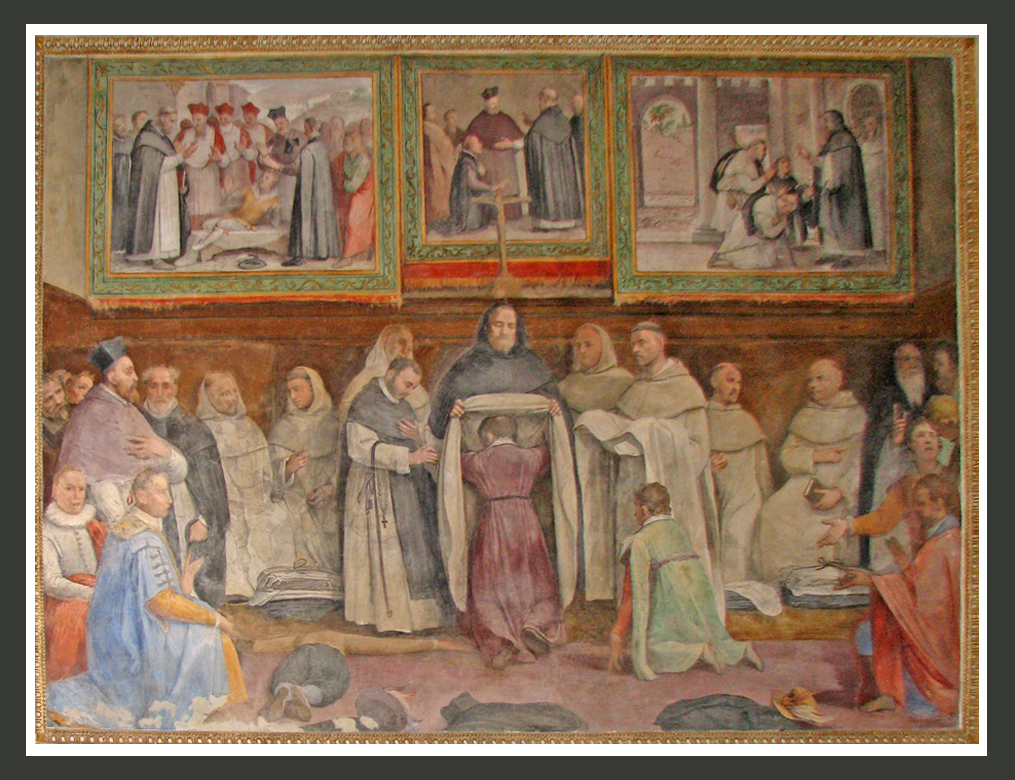

The novices make the form of a Cross, as a sign of the total gift of themselves to the service of the God and His Church in the footsteps of St Dominic.

The novices make the form of a Cross, as a sign of the total gift of themselves to the service of the God and His Church in the footsteps of St Dominic.