On 28 June, Br Lawrence Lew OP was invited to speak to the Dominican Family on preaching through music. Below is an abridged version of his talk with pictures from the day, which took place at the

Niland Conference Centre in Bushey near London:

In that gospel of Matthew which our holy father Dominic loved and carried with him, we read that after the Last Supper, Jesus and his apostles sang a hymn and then went to the Mount of Olives. In the Acts of the Apostles, we read that when Paul and Silas were imprisoned in Philippi, they prayed and sang hymns to God, and the prisoners listened to them. In Colossians 3:16, St Paul instructs the Christian community to “sing psalms and hymns and spiritual songs with thankfulness in your hearts to God”. Hence Joseph Ratzinger has said that: “Right from the beginning liturgy and music have been closely related [for] wherever people praise God, words alone do not suffice.” St Augustine said that “only he who loves can sing” and the Christian is one who loves the God who has first loved us. Therefore because music expresses our Christian joy in salvation and hope of eternal life, it is right that it plays such a central role in our lives and worship. Moreover, as Timothy Radcliffe OP has said, “Music overcomes the darkness and speaks a hope for what we cannot imagine”. Music is thus a powerful form of preaching.

In the Dominican tradition we have a story in which St Dominic’s successor, Blessed Jordan of Saxony, exhorts the novices to laugh and be merry because they have been “saved from the Devil’s thralldom”. Paul Murray OP comments that this story “serves to underline something really fundamental about the early Dominicans and their fresh grasp of the Gospel. Throughout the preaching ministry of Dominic, a vision of Gospel joy had come to define itself over and against some very grim and very gloomy notions indeed.” He goes on to say that “the deep, almost uncontrollable laughter which springs from Gospel joy… is, in fact, simply an ecstasy of the inner heart… an impulse of surrender and delight towards the neighbour and towards God.” For Dominic, his Gospel joy is expressed in his life through his impulse to preach. However, the stories about St Dominic recount that his joy was also frequently expressed in song, and it is reported that he sang as he traveled throughout Europe. Singing and preaching are closely related for both find their root in Gospel joy and this joy that bursts forth as laughter also bursts forth as wordless song.

Let us consider the words of St Augustine in this regard. He says: “‘Shout for joy… sing a new song’ (Ps 33:3). What would this song of joy mean? It means something that cannot be explained in words: it is what the heart is singing… those who start singing [ ] while they are eagerly carrying on some other work, start with the words of a song to express their joy, but then it is as though they are overcome with such happiness that words no longer can express it and they leave out the words and simply give themselves over to sounds of jubilation… [God who is ineffable] not only cannot be expressed in words but also cannot be passed over in silence, and so, what can one do but jubilate? For in jubilation the heart opens up to joy without words, and that joy widens out immeasurably beyond the utmost reaches of our words.”

St Paul sees this outpouring of love as something caused by the Holy Spirit, and so he writes to the Church at Ephesus, saying: “be filled with the Spirit, addressing one another in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing and making melody to the Lord with all your heart”. I will return to St Augustine’s exhortation to wordless jubilation in due course, but for now, let us consider St Paul’s instruction. It is noteworthy that he says we should sing to one another, for there is a sense here of holy preaching in song. If we think about it, isn’t this precisely what we do when we sing the Divine Office antiphonally? For then we address one another in psalms, hymns and sacred songs, and so, we recall and preach the

mirabilia Dei to one another. Seen in this way, the sung Liturgy is an important kind of holy preaching that we, gathered as the Body of Christ, can perform together. Truly then, singing the Office, is a kind of preaching that all of us – lay and ordained – can share in.

Timothy Radcliffe OP has said that “the singing of the liturgy… discloses the meaning of our lives”, and this is true because our song is an expression of the joy and hope that is the bedrock of our Christian lives. Music, which is marked by form, structure, rhythm and shape is a discipline, and so, Timothy also suggests that it points to the kind of life we are called to lead, that is, the virtuous life. Thus, “St Augustine thought that to live virtuously was to live musically, to be in harmony.” Music that is harmonious is beautiful, just as virtuous lives are beautiful, and such beauty gives praise to God who is beauty. In this regard, Timothy goes on to say that “if the Church is to offer hope to the young, then we need a vast revival of beauty in our churches” and we can begin with re-beautifying our Church music. I would agree with Timothy that “much modern music, even in Church, is so trivial that it is a parody of beauty” and he suggests that the Church is called to be “a place of the revelation of true beauty” for then, God is revealed, and God is preached through beauty. Joseph Ratzinger has said much the same. He says: “The Church is to transform, improve, ‘humanize’ the world – but how can she do this if at the same time she turns her back on beauty, which is so closely allied to love? For together, beauty and love form the true consolation in this world, bringing it as near as possible to the world of the resurrection. The Church must maintain high standards; she must be a place where beauty can be at home”. Therefore, it is clear that we need to re-discover beauty in the Church and particularly beauty in song.

Let us return to St Augustine. You may recall that he said that Christian joy spills over into an inexpressible song of joy. St Paul sees this song as being inspired by the Holy Spirit, and one can think of the great outpouring of the Spirit at Pentecost. Then, the Spirit inspired the apostles to speak in tongues and to babble with joy. The Spirit filled the disciples with such joy that they burst forth in song and so St Ephrem compared the disciples at Pentecost to small birds. This same Spirit fills the Church so that she bursts forth in song and we are singers of the Church’s song; we become little birds. Thus Simon Tugwell OP considers this kind of joyful singing as “words released in us by the Holy Spirit [which] are primordial words; words which spring from our creatureliness as deeply and simply and inexplicably as birdsong”.

What is this wordless song that the Spirit inspires and what might it sound like? We can clearly hear this characteristic in Gregorian chant, whereby words give way to pure music, called a

melisma or

jubilus. Daniel Saulnier OSB describes this as “a moment of pure music that blooms on a syllable” and he says that “this manner of singing and of pouring out one’s inner life by means of a vocalise that transcends the limits of syllables, and therefore, of thoughts, is probably as old as humanity.”

Melisma is of such importance to plainsong because it is a jubilation, a sacramental sign of the inner joy that inspires all Christian song; it is an expression of sacred song inspired by the Holy Spirit.

As song that is inspired, it was also written down and preserved for the good of the Church, that it might be handed down and sung in every age. Thus, Pope Pius X said that “Gregorian chant [is] the only chant she [the Church] has inherited from the ancient fathers” and so, Vatican II says, it is “specially suited to the Roman liturgy”. If we recognize plainsong as inspired music that has been written and handed down, then we could perhaps see it as being analogous to the Scriptures. For just as the Spirit once inspired human beings to write down sacred texts and hand them down in the Church, so the Spirit also inspired human beings to write down sacred song and it forms a vital part of the Church’s tradition. Both the Scriptures and chant, then, are rightly used in our preaching. It is this marriage of the inspired word of God and inspired song, found in the Church’s treasury of sacred music, that has moved the Fathers of Vatican II to call it “a treasure of inestimable value, greater even than that of any other art.”

Just as plainsong and its melismas capture a moment of inspired song, so we might hear polyphony as an evocation of singing in tongues that thus captures the beauty and harmony of the Pentecost moment. In polyphony, each voice is unified by the text but each sings a different melody so that together they create something greater than the sum of its parts. This musical form has something to teach us because preaching the gospel, studying theology and the exercise of ministry in the Church, I would suggest, should also be polyphonic. In this way, we mirror St Paul’s idea that the Church is like a body made up of many parts who need one another and serve the growth and progress of the entire organism. This is also true when we act polyphonically, singing the same gospel song but with the harmonious contribution of our different voices.

C.S. Lewis said that in hell there is neither silence nor music. It is not accidental that he should link the two, because music, as we have seen, is the gift of the Spirit and it seems to me obvious then, that music is the fruit of silence. In the first book of Kings, we recall that God’s still small voice was heard in the silence. Therefore, silence is a necessary pre-condition of listening, of being inspired, or encountering the beauty of God and thus, of making music. There is a Dominican motto:

silentium pater praedicatorum, silence is the father of preachers, and this motto draws on the same idea, for preaching and music both flow from silence, and this is to be expected, as both are inspired by the Spirit. Moreover, Josef Pieper points out that music, “to the extent that it is more than mere entertainment of intoxicating rhythmic noise”, creates a kind of “listening silence” and opens up a space in which we encounter beauty, and so can experience God. Gregorian chant and the Church’s sacred treasury of music is precisely this kind of music that flows from silence, encourages contemplation of the Word and opens up a space in which we can find God. Church music, then, is a kind of holy preaching because it encourages us to listen to the Word, and teaches us to seek God in silence and contemplation.

The appreciation of beauty born of contemplation is something that our noisy world has to re-learn and this education begins with us in the Church. Timothy Radcliffe suggests that we have lost sight of beauty because we “fall into the trap of seeing beauty in utilitarian terms, useful for entertaining people, instead of seeing that what is truly beautiful reveals the good.” I believe that Gregorian chant and polyphony challenges us to really listen, to transcend merely entertaining music, and to glimpse the mystery and beauty of God. Finally, Pope John Paul II leaves us with food for thought, something to inspire us to cultivate and to draw from the treasury of sacred music and hopefully, to pray and contemplate with music. He said: “As a manifestation of the human spirit, music performs a function which is noble, unique and irreplaceable. When it is truly beautiful and inspired, its speaks to us more than all the other arts of goodness, virtue, peace, of matters holy and divine.” And this, surely, is the hope and goal of the preacher?

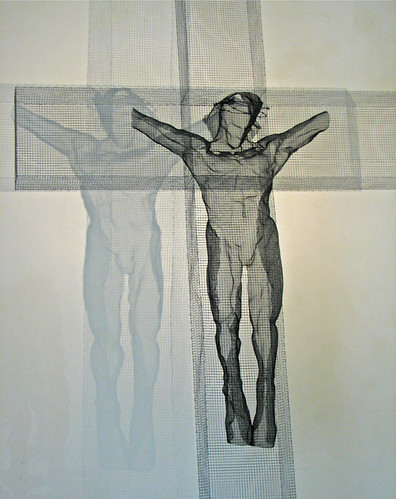

Pilgrimage can also be a way of discovering that ascetic dimension to life, a dimension in which in one way or another, all Christians are called to participate. Christ showed his great love for us by dying on the cross, and so in a small way by doing something arduous and renouncing ourselves, we can show our love for Christ and grow in the virtue of charity.

Pilgrimage can also be a way of discovering that ascetic dimension to life, a dimension in which in one way or another, all Christians are called to participate. Christ showed his great love for us by dying on the cross, and so in a small way by doing something arduous and renouncing ourselves, we can show our love for Christ and grow in the virtue of charity.

On arriving at the Slipper Chapel, we prayed to Our Lady for the conversion of England and Wales, before going into Mass in the Chapel of Reconciliation. We then walked the final mile into Walsingham, praying the Rosary as we went, joyful in the anticipation of reaching our final destination. Our pilgrimage came to an end with Benediction in the Church of the Annunciation in Walsingham; it was a chance to focus on our final goal, life with Christ, and an opportunity to be thankful for the many graces which we had received through the prayers of Our Lady of Walsingham on our pilgrimage.

On arriving at the Slipper Chapel, we prayed to Our Lady for the conversion of England and Wales, before going into Mass in the Chapel of Reconciliation. We then walked the final mile into Walsingham, praying the Rosary as we went, joyful in the anticipation of reaching our final destination. Our pilgrimage came to an end with Benediction in the Church of the Annunciation in Walsingham; it was a chance to focus on our final goal, life with Christ, and an opportunity to be thankful for the many graces which we had received through the prayers of Our Lady of Walsingham on our pilgrimage.

Pilgrimage can also be a way of discovering that ascetic dimension to life, a dimension in which in one way or another, all Christians are called to participate. Christ showed his great love for us by dying on the cross, and so in a small way by doing something arduous and renouncing ourselves, we can show our love for Christ and grow in the virtue of charity.

Pilgrimage can also be a way of discovering that ascetic dimension to life, a dimension in which in one way or another, all Christians are called to participate. Christ showed his great love for us by dying on the cross, and so in a small way by doing something arduous and renouncing ourselves, we can show our love for Christ and grow in the virtue of charity.

On arriving at the Slipper Chapel, we prayed to Our Lady for the conversion of England and Wales, before going into Mass in the Chapel of Reconciliation. We then walked the final mile into Walsingham, praying the Rosary as we went, joyful in the anticipation of reaching our final destination. Our pilgrimage came to an end with Benediction in the Church of the Annunciation in Walsingham; it was a chance to focus on our final goal, life with Christ, and an opportunity to be thankful for the many graces which we had received through the prayers of Our Lady of Walsingham on our pilgrimage.

On arriving at the Slipper Chapel, we prayed to Our Lady for the conversion of England and Wales, before going into Mass in the Chapel of Reconciliation. We then walked the final mile into Walsingham, praying the Rosary as we went, joyful in the anticipation of reaching our final destination. Our pilgrimage came to an end with Benediction in the Church of the Annunciation in Walsingham; it was a chance to focus on our final goal, life with Christ, and an opportunity to be thankful for the many graces which we had received through the prayers of Our Lady of Walsingham on our pilgrimage.