For the feast of the Holy Family, the first Sunday of Christmas, His Grace Archbishop Bernard of Birmingham, sent out a pastoral letter to be read out at all churches and chapels of the archdiocese. In order to share His Grace's insight we here at Godzdogz have reproduced some of the key points of the letter, a link to the full letter can be found at the bottom of the post.

----

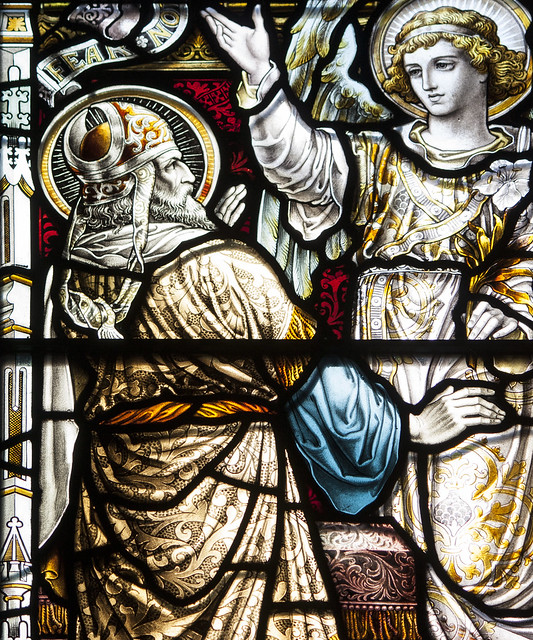

|

| Archbishop Bernard |

At Christmas we have been celebrating a divine mystery revealed to us in the ordinary circumstances of the life of a family. The Incarnation is a sublime exchange in which God becomes man so that our humanity can be drawn deeper and deeper into the life of God. .. The extraordinary truth of Christmas is that all of this has taken place within a setting that is familiar to us and in the humblest of circumstances. … Within his people Israel it wasn’t from among the powerful or influential that God identified a family for his Son Emmanuel, but it was a poor girl who was capable of great love that God invited to become the mother of his Son. The family setting for Jesus’ birth was the loving and trusting relationship between Mary and Joseph and the difficult circumstances in which they found themselves from the outset.

This teaches us something about the unfathomable humility of God, that the maker and ruler of all that exists should choose to come among us in a setting that had such apparent disadvantages… The story of the Holy Family is full of encouragement for those who struggle in life – especially in their family life – and it enables us to see that true riches lie within our relationships and not in our abilities or possessions.

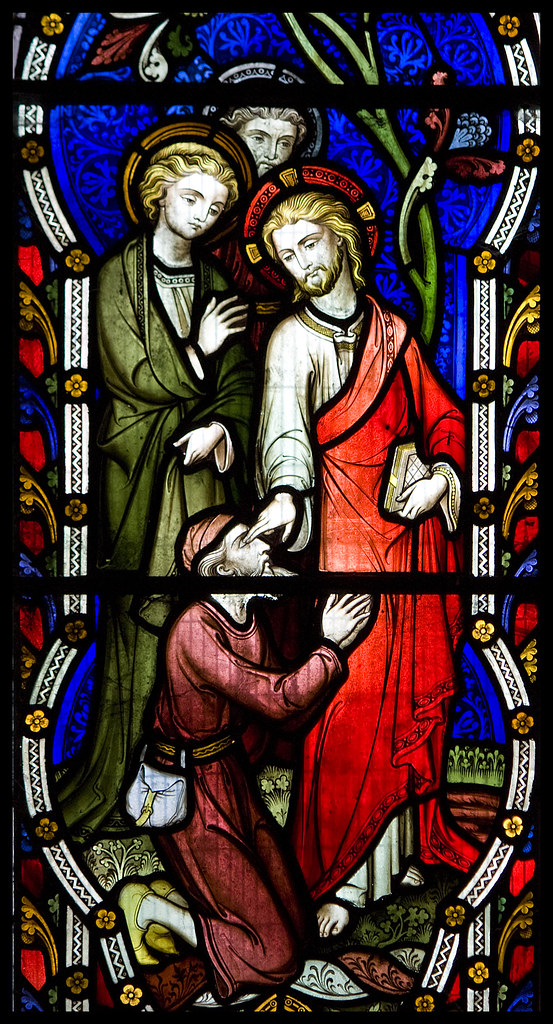

Those bonds of love that held Jesus, Mary and Joseph together as a family formed the first human relationships that the Word-made-flesh would know. Like all of us Jesus was shaped in his expectations of life and in his outlook towards others by what he heard and saw as a child at home. We learn much about his own family from our Lord’s teaching and in his attitudes towards a wide range of people.

In Mary and Joseph our Lord came to understand what it means to love God above all things and to love our neighbour as ourselves… Despite the hardships that surrounded the birth of their child Mary and Joseph did not grow cynical or suspicious of the world around them and they communicated this generous outlook in their family life. Jesus grew up looking for goodness in others because he had first experienced this search for goodness within his own family. From within his family our Lord began to show the depths of the Father’s love: God so loved the world that he gave his only Son. (John 3:16)

The example of the Holy Family and their experiences of misunderstanding and rejection remind us of the need for understanding and compassion - especially for those who have experienced a break-down of family life or who may have become estranged from their closest relatives… It was surely his own experience of family life that enabled our Lord to see that it is not the healthy who need a doctor, but the sick. (Luke 5:31)

|

In Mary and Joseph our Lord came to understand what it means to love God above all things and to love our neighbour as ourselves… Despite the hardships that surrounded the birth of their child Mary and Joseph did not grow cynical or suspicious of the world around them and they communicated this generous outlook in their family life. Jesus grew up looking for goodness in others because he had first experienced this search for goodness within his own family. From within his family our Lord began to show the depths of the Father’s love: God so loved the world that he gave his only Son. (John 3:16)

The example of the Holy Family and their experiences of misunderstanding and rejection remind us of the need for understanding and compassion - especially for those who have experienced a break-down of family life or who may have become estranged from their closest relatives… It was surely his own experience of family life that enabled our Lord to see that it is not the healthy who need a doctor, but the sick. (Luke 5:31)

The Holy Family embraces us, with all our imperfections, so that we may long for and find healing and perfection in Christ. May the Holy Family of Nazareth inspire and encourage us to be true to Christ and to reflect his mercy in the world and in our own family homes. Let the message of Christ, in all its richness, find a home with you.

----