“Never discuss religion and politics”, they say. So one would appear to be straying into dangerous territory in seeking to discuss economic justice and the dignity of the worker in the context of Catholic Social Teaching; for if ever there was an area in which the taboo two meet head on, it is surely this?

In any event I often used to find at dinner parties that politics would come up, perhaps with the other guests hoping, in vain, that if they let me talk about politics they would not have to hear me out on religion. Conversation would inevitably involve one half of the table railing against the plight of the poor and the need for greater welfare provision, whilst the other half would talk about the evils of state welfare dependence, and need to empower people and reduce government intervention in people’s lives. Unwittingly, both positions point to the two pillars of Catholic Social Teaching: solidarity and subsidiarity.

Subsidiarity, implied throughout the whole of Catholic social theory and given its clearest expression in Pope Pius XI's encyclical Quadragesimo Anno, means that in the adjudication of matters political and economic, a preferential option should be given to the more local level of authority. The state should not interfere in matters in which people are competent to decide for themselves. Furthermore the state should not presume its citizens are incompetent to determine what is best for them just because they are poor as this undermines their intrinsic dignity.

However, subsidiarity must always be balanced by solidarity, which is to say, a keen sense of the common good, of the natural and supernatural connections that bind us to one another, of our responsibility for each other. The message of the parable of the Good Samaritan is not vitiated by subsidiarity. Nor, as many point out, should the state discourage the individual from helping others; the elimination of charity is not the aim of solidarity. Nevertheless, the concept of solidarity acknowledges that sometimes the government is the legitimate vehicle by which social solidarity is achieved. There are things that we cannot achieve as individuals at a small community level, but which we can achieve on a larger scale with combined efforts and resources. However, it must always be remembered that “solidarity is first and foremost a sense of responsibility on the part of everyone with regard to everyone, and it cannot therefore be merely delegated to the State” (Caritas in Veritate).

“Thus the principle of subsidiarity must remain closely linked to the principle of solidarity and vice versa, since the former without the latter gives way to social privatism, while the latter without the former gives way to paternalist social assistance that is demeaning to those in need” (Caritas in Veritate) . . . the aforementioned dinner party tension!

Where though does economic justice fit into all this, and what might the Church usefully have to say about it? Is the Church even qualified to have an opinion on such matters? Well, almost no one predicted the global financial crisis which came to a head in 2008, including most economists, although in an interview back in 1996 when asked his opinion, on the Western economic system and its then trajectory, one churchman gave the following perceptive analysis, showing that we might just be worth listening to on such matters:

As a matter of fact, I understand too little of the world's economic system to say. But it is apparent that in the long run it can't continue as it is. First of all, there is the inner contradiction of the indebtedness of states, which live in a paradoxical situation; for, on the one hand, they issue money and, in general, guarantee the value of money but, on the other hand, are actually bankrupt, if we judge in terms of the debts. There is, of course, also the debt disparity between North and South. All of this shows that we live in a whole network of fictions and contradictions and that this process cannot continue on indefinitely.

"We have just witnessed [Spring 1996] this curious situation in America. Suddenly the state can no longer pay its debts and must close shop, so to speak, and furlough its civil servants, which is a crying contradiction because the state has the responsibility for holding the whole together. The incident has shown in a drastic way that our system contains gross mistakes and that a considerable effort is required to find the corrective elements.

This critique of the prevailing system is characteristic of much Catholic Social Teaching on economic justice. It is not prescriptive, respecting their legitimate autonomy on such matters; it does not give detailed requirements of how states are to organise themselves, but rather with the benefit of critical distance identifies trends; what is potentially positive in them; what is less desirable; and also where excesses may lead.

Seeking to proclaim the truth in and out of season, inevitably finds the Church often teaching against the prevailing consensus; accusations have been levelled that its teaching on economic justice has been both in favour of Marxism and unbridled capitalism. The truth though is that when the Church looks at economic justice it never does so from a purely economic point of view. This point is key. The Church refuses to see the human person as purely an economic agent or utility maximiser. We are so much more than this and public policy must take this into account, as Pope St John Paul II sets out in Centesimus Annus:

The economy in fact is only one aspect and one dimension of the whole of human activity. [Where] economic life is absolutised, [and] the production and consumption of goods become the centre of social life and society's only value, not subject to any other value, the reason [for this] is to be found not so much in the economic system itself as in the fact that the entire socio-cultural system, by ignoring the ethical and religious dimension, has been weakened, and ends by limiting itself to the production of goods and services alone.

All of this can be summed up by repeating once more that economic freedom is only one element of human freedom. When it becomes autonomous, when man is seen more as a producer or consumer of goods than as a subject who produces and consumes in order to live, then economic freedom loses its necessary relationship to the human person and ends up by alienating and oppressing him.

Thus any public policy which fails to take in account what it means to be human and to flourish fully as a human being, not just as an economic agent, is never going to benefit society truly. The idea that if we just get the economic system right everything else will take care of itself which seems relatively uncontested across all political parties at present is what Pope Francis rails against in Evangelii Gaudium. He asks the jolting question:

How can it be that it is not a news item when an elderly homeless person dies of exposure, but it is news when the stock market loses two points?

neatly illustrating the warped mentality that has led us in many cases to believe that we are ruled by the financial systems in place rather than their being at our service, as if somehow we did not have the free will to act differently and economic events just happen to us. We need to change, not just the system in the abstract.

He then goes to on to criticise the idea that if one segment of society gets richer everyone else will automatically benefit:

“. . . some people continue to defend trickle-down theories which assume that economic growth, encouraged by a free market, will inevitably succeed in bringing about greater justice and inclusiveness in the world. This opinion, which has never been confirmed by the facts, expresses a crude and naïve trust in the goodness of those wielding economic power and in the sacralised workings of the prevailing economic system. Meanwhile, the excluded are still waiting. To sustain a lifestyle which excludes others, or to sustain enthusiasm for that selfish ideal, a globalization of indifference has developed. Almost without being aware of it, we end up being incapable of feeling compassion at the outcry of the poor, weeping for other people’s pain, and feeling a need to help them, as though all this were someone else’s responsibility and not our own. The culture of prosperity deadens us; we are thrilled if the market offers us something new to purchase. In the meantime all those lives stunted for lack of opportunity seem a mere spectacle; they fail to move us.”

Some cheap headline seekers have sought to suggest that is the Pope saying that capitalism is wrong and advocating Marxism, however, this is badly to miss his point. What he is saying is that we can never delegate our responsibilities of justice, fairness and a concern for the poor, to the system. We, at an individual and a societal level, always have moral responsibilities to those around us, which no system, no matter how fair, will ever abrogate. As EF Schumacher wrote: “The economic problem . . . is a problem which has been solved already; we know how to provide enough and do not require any violent, inhuman, aggressive technologies to do so. There is no economic problem and, in a sense, there never has been. But there is a moral problem, and moral problems . . . are not capable of being solved so that future generations can live without effort.”

What particularly alarms me as we move beyond the economic crisis of 2008 is how wealth inequality is growing at an unprecedented rate once more, and there seems to be a presumption from some that if only the rich become even richer, the poor will eventually benefit. Eventually in and of itself is not good enough, irrespective of the absence of evidence that this will in fact eventually happen. Economic justice, not only demands that change occur to those structures of inequality that mean that those who were in large part responsible for the crash are the first to recover from it, but also that those currently reaping rewards do not ignore the plight of those less fortunate and assume that somehow they will be okay . . . eventually. We have a responsibility towards our fellow members of society that should compel us to do something now.

As the US Bishops have written on economic justice: “Our faith calls us to measure [the] economy not only by what it produces, but also by how it touches human life and whether it protects or undermines the dignity of the human person. Economic decisions have human consequences and moral content; they help or hurt people, strengthen or weaken family life, advance or diminish the quality of justice in our land.” We need as a society to become more keenly aware of all these aspects, and we need to do this quickly. At the same time as advocating for fairer systems, we must not lose sight of the fact that we can have an impact at an individual level too. We can think about where we shop and who benefits, if we have responsibility for setting somebody’s wages this also should give us pause for thought.

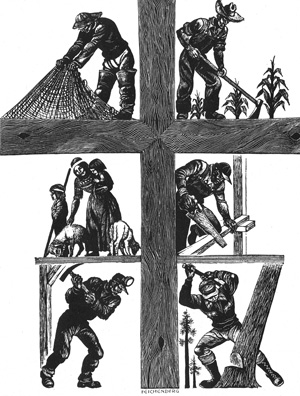

Today being the Feast of St Joseph the Worker, in this context, I want to reflect briefly on the dignity of the worker. The Church has always seen the dignity of work in and of itself. Work is not just viewed as a means to an end, but as something which has worth in and of itself. This is why we should never be content about having large numbers of people out of work, even if the benefits given to them were sufficient to support them and their dependents. There is a justifiable sense of self-worth to be derived from work and furthermore anybody who has ever watched The Jeremy Kyle Show will know that there is at least one good reason not to be idle at home during the day!

|

| Mosaic of St Joseph the Worker, with Jesus and Mary |

In Laborum Exercens, Pope St. John Paul II looks on work not just as a means of self-support but also as a contribution to society and one way in which Man is distinguished from the rest of Creation:

“Through work man must earn his daily bread and contribute to the continual advance of science and technology and, above all, to elevating unceasingly the cultural and moral level of the society within which he lives in community with those who belong to the same family. And work means any activity by man, whether manual or intellectual, whatever its nature or circumstances; it means any human activity that can and must be recognized as work, in the midst of all the many activities of which man is capable and to which he is predisposed by his very natures, by virtue of humanity itself. Man is made to be in the visible universe and image and likeness of God himself, and he is placed in it in order to subdue the earth. From the beginning therefore he is called to work. Work is one of the characteristics that distinguish man from the rest of creatures, whose activity for sustaining their lives cannot be called work.”

This is a very different conception of work and the worker from the mindset, all too prevalent, which sees the worker as a merely another production cost. Employers need to realise that their workers are human being with lives and aspirations outside of their work. Wages should never be viewed as just another necessary expenditure to be cut as far as possible for the sake of the profit margins. The argument that says paying higher wages, where people would work for less, is a dereliction of the duty to act in the interest of the shareholders rests on a selfish conception of the shareholder as one who is only interested in his own profits. If , though, we are to flourish fully as human beings this cannot be the dominant mindset. Nor is this pure pipedreaming, there are companies out there that treat staff equitably and continue to flourish in a difficult trading environment, John Lewis springs to mind.

The shrewd analyst who predicted the economic crash back in 1996 (Joseph Ratzinger) had something further to say on remedying the prevailing economic system:

“But I would like to add that we will not find [the corrective elements for our economic system] if there is no common capacity for sacrifice. For these correctives cannot simply be created by government prescription.

"This is the great test of strength for societies. We must learn that we cannot have everything we would like, that we must also go a notch below the standard that we have reached. We must once again find our way beyond what we currently possess, beyond the defence of our rights and claims. And this transformation of hearts is needed in order to make sacrifices for the future and for others. This, I think, will be the real acid test of our system.”

|

| Christ crucified - the ultimate sacrifice |

For the ultimate example of sacrifice, we need look no further that the inspiration behind all Catholic Social Teaching, Jesus.