Readings: Mark 11: 1-10; Isaiah 50: 4-7; Psalm 22: Philippians 2: 6-11; Mark 14:1-15:47

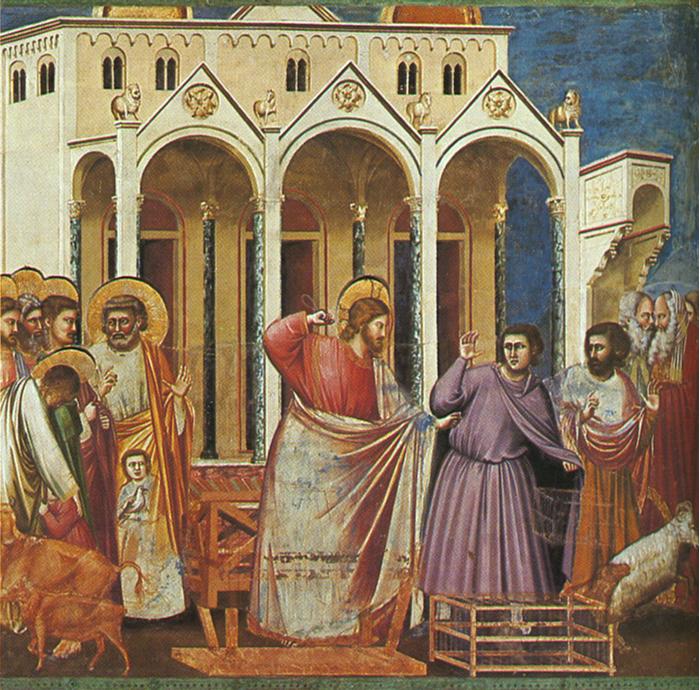

In the space of a few days, Jesus went from being hailed as a hero to being condemned as a criminal, and today’s Palm Sunday liturgy dramatically captures this change in the crowd’s perception of Jesus. To understand why there was such a radical change in the crowd’s perception, we can look to the passages in St Mark’s Gospel which describe Jesus’ final few days in Jerusalem.

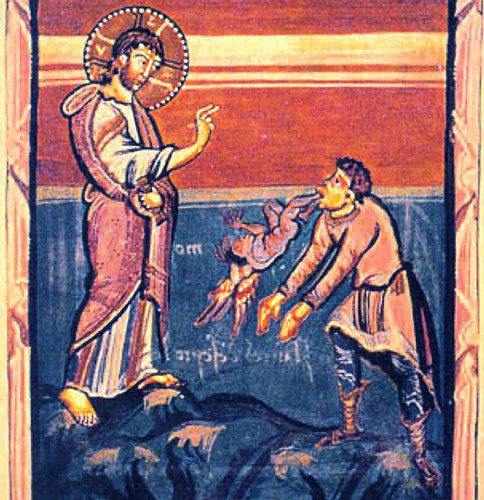

In the space of a few days, Jesus went from being hailed as a hero to being condemned as a criminal, and today’s Palm Sunday liturgy dramatically captures this change in the crowd’s perception of Jesus. To understand why there was such a radical change in the crowd’s perception, we can look to the passages in St Mark’s Gospel which describe Jesus’ final few days in Jerusalem.The reason is to do with the kind of Messiah they were expecting. The crowd’s expectation was of a worldly Messiah, a Messiah who would rescue them from their Roman oppressors and reaffirm their identity as God’s holy people. But Jesus not only refused to lead a rebellion against the Roman authorities, but he challenged them on their very identity, which they were expecting Jesus to affirm. Jesus tells the Jews to pay their taxes to Caesar, he describes the chief priests, the scribes and the elders, in terms of vineyard tenants who are soon to be evicted, and he predicts the destruction of the temple. So given their expectations, Jesus was saying all the wrong things. Nevertheless, Jesus is still their Messiah. He is still the Saviour of his people. The problem was not with anything Jesus said: the problem was with the kind of Messiah the crowd expected, and how they believed the Messiah would save them.

This question of what kind of Messiah to expect is at the heart of Christianity. It is so easy for us to get caught up with the culture of our day, so that our hopes and aspirations become indistinguishable from the worldly hopes and aspirations of those around us. Or perhaps we are so disillusioned with the world that we seek to be free from the constraints we feel the world places on us. But if these are our ultimate expectations, if this is what we expect Jesus to do for us, then we are going to be sadly disappointed. If we try to make Jesus into what we want him to be, we’re going to fail, and the Cross is the sign of our failure.

But rather, we have to let Jesus make us into what he wants us to be, and the Cross is the sign of his power to transform us; his outstretched arms on the Cross show God’s healing love towards us. When his precious blood flowed from his side, the Holy Spirit flowed out into the world. We became able to participate in the inner life of the Trinity. By the grace that we receive through Christ’s Passion, our human nature is perfected and conformed to the divine nature.

It can be very painful letting go of our hope for comfort, security, and recognition by others, but what Jesus gives us is infinitely greater: through and in Jesus Christ it is humanly possible to know and love God.