Last week, on Tuesday 25 October, William Lane Craig had hoped to debate Richard Dawkins at the Sheldonian Theatre. But our most public atheist didn't show up,

exactly as he'd promised. Instead, the American Christian philosopher gave us a lecture criticising Dawkins' book, The God Delusion, as he pursued the basic objective of his Reasonable Faith tour of the UK: to persuade us that (Christian) theistic belief is intellectually respectable.

Professor Craig gave a lively presentation of the classical arguments for God's existence – Cosmological, Moral, Teleological and Ontological. These arguments have seen a renaissance in recent decades, strengthened by current scientific theories about the origin of the cosmos and by new philosophical arguments, such as Alvin Plantinga’s ‘possible worlds’.

Professor Craig gave a lively presentation of the classical arguments for God's existence – Cosmological, Moral, Teleological and Ontological. These arguments have seen a renaissance in recent decades, strengthened by current scientific theories about the origin of the cosmos and by new philosophical arguments, such as Alvin Plantinga’s ‘possible worlds’.

So it is odd, said Craig, that so many people believe The God Delusion has actually won the argument against God. The problem is, Dawkins’ aim is explicitly polemical– he wants to convert the reader to atheism – so he shies away from certain philosophical conundrums: for instance, he surprisingly fails even to mention the ‘argument from contingency’, the most common form of the cosmological argument.

Craig triumphantly remarked that Dawkins does not fully dispute the philosophical argument (that a personal First Cause might exist); indeed, on the atheist scale Dawkins puts himself at 6 out of 7. Craig, convinced that Christianity is rationally defensible, even plausible, can hardly be surprised by this. Perhaps stronger arguments against God could be found, he admitted cautiously, but Dawkins certainly does not provide them.

Next came the responses from the panel – all Oxford academics. Daniel Came, the atheist philosopher who had challenged Dawkins to debate against Craig, discussed actual and potential infinities and defended the qualitative parsimony of the ‘multiverse’ theory, remaining at least a ‘sceptical agnostic’.

Stephen Priest (of Blackfriars Hall) stunned the audience with his provocative declaration that philosophy stalled in the 18th century and that none of its deepest questions (Time, Being, Selfhood) can be answered without the aid of theology and spirituality. Spiritual knowledge (the best sort) is about personal acquaintance, not propositions.

John Parrington, an atheist pharmacologist, was also illuminating, if not as strictly philosophical. He suggested that all the talk about cosmological arguments might be indicating a retreat of religion towards deism: we talk about the origin of the universe because we’ve stopped talking about the hand of God in everyday life all around us. In Parrington’s field, he said, biological mechanisms don’t need a divine Designer or Sustainer; at most they may allow a distant Deist God.

Indeed, it is the ‘central argument’ of The God Delusion that postulating God as an ‘intelligent designer’ of the universe is less plausible than having no designer. As Dawkins says, ‘Who designed the Designer?’ This, however, was rebutted by Dr Came: by its nature an explanation doesn’t need further explanation. If the Designer provides any explanation at all, that is enough.

I think a biographical note may shed some light here. Dawkins’ boyhood Christianity, by his own account, was entirely based on the idea of God as the designer of nature, like a celestial gardener. As he progressed in biology, the young Dawkins saw that nature contains in itself the mechanisms for its own operation, rendering God an unnecessary ‘hypothesis’, as Laplace once said to Napoleon. All the doctrines and daily practices of Christianity – the Virgin Birth, the Resurrection, the Trinity, petitionary prayer, the value of the Bible, raising children as Christians, and so on – became in Dawkins’ view an unjustifiable charade, requiring no further disproof.

But here’s the rub: orthodox Christianity rejects the ‘celestial gardener’ too. The Judaeo-Christian tradition has handed down the basic insight that God is One and perfectly transcendent. He is not a being, on the same scale as objects and persons in the universe, but perfect Being itself. Since Dawkins’ Christian faith did not mature into adulthood, his idea of ‘God’ has not developed either. Unless Dawkins takes theology seriously, to engage a fully Christian account of God, his is necessarily a weak atheism.

The irony is that Craig, like Dawkins, did not attribute full perfection to God. In his response to Priest, two serious problems emerged in Craig’s position: he claimed that God is a being (though not ‘a chap’ like the celestial gardener); and that God changes in time, in his activities and knowledge, once the universe is created. It is strange that Craig, after eloquently defending divine simplicity, omniscience and timelessness, should then contradict himself with this imperfect idea of God as changeable in time like any other being. This is impossible if we follow the classic Christian account of God as self-identical, self-subsisting existence (ipsum esse per se subsistens), as St Thomas Aquinas puts it. God’s existence and essence are identical: “I Am That I Am” (Ex. 3:14).

One questioner asked about Craig’s defence of God’s command to slaughter the Canaanites (Deut. 20:13-18), or at least dispossess them of their land. This apology for ‘genocide’ is the putative reason why Dawkins refuses to meet Craig in debate. This is a grave matter, and it is not enough to point out, as Craig did, that Dawkins himself holds incoherent views on morality (Dawkins claims there are no objective moral values, ‘nothing but blind pitiless indifference’, yet simultaneously expresses moral outrage at the religious ‘indoctrination’ of children (for instance) and stands by a set of 10 New Commandments).

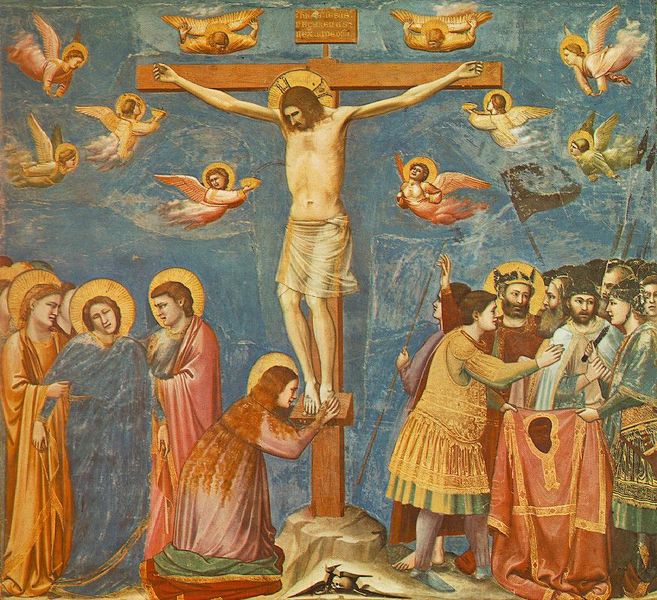

Craig’s answer on the night summarised his earlier articles; see the links above. Suffice to say, this was another weak point. He suggests it is our ‘Christianized, Western standpoint’ that makes us morally squeamish about the ‘brutal’ life of ancient peoples. But a Christian perspective is exactly what we need here. The direct slaughter of innocents is always and everywhere wrong; so the killing of Canaanite children (if it happened) is repugnant. A more constructive question, then, is not ‘Was it justified?’ but ‘How can these disturbing episodes be understood in the context of God’s universal plan for the salvation of mankind?’ – that is, in the light of the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ, the definitive self-revelation of God.

Perhaps a less sympathetic audience or panel would have pressed these matters further. The final question asked for a show of hands: who believes in a Creator God, who disbelieves, who is unsure, and who does not care? The vast majority, over 90% by my estimate, were believers. If Professor Craig was speaking largely to the converted, hosted as we were by the Christian Union and Premier Christian Radio, the challenge is now to convince other people, by the same rational argument and faithful witness, that Christianity is reasonable faith.

On the 1st December 1581 Edmund Campion, alongside two of his brother priests, suffered execution at Tyburn. He was forty-one years old. His life, though short, was truly remarkable, and it is not without good reason that his name is still remembered so well and his sacrifice duly honoured. Campion was a gifted scholar, educated at Christ’s Hospital, London and St John’s College, Oxford where he became a junior fellow aged only seventeen. It was whilst at Oxford that he won the attention of Queen Elizabeth and the patronage of the highly influential William Cecil. He consequently became a deacon in the established church, though his discomfort at doing so took him to Ireland where he pursued more study and finally to Douai in the Low Countries where he was ultimately reconciled with the Catholic faith.

On the 1st December 1581 Edmund Campion, alongside two of his brother priests, suffered execution at Tyburn. He was forty-one years old. His life, though short, was truly remarkable, and it is not without good reason that his name is still remembered so well and his sacrifice duly honoured. Campion was a gifted scholar, educated at Christ’s Hospital, London and St John’s College, Oxford where he became a junior fellow aged only seventeen. It was whilst at Oxford that he won the attention of Queen Elizabeth and the patronage of the highly influential William Cecil. He consequently became a deacon in the established church, though his discomfort at doing so took him to Ireland where he pursued more study and finally to Douai in the Low Countries where he was ultimately reconciled with the Catholic faith.

Two of the most obvious and controversial changes in the new translation relate to the consecration of the precious blood. To begin the translation of Pro Multis is now rendered as "for many", whilst before it was translated "for all". This is closer to the synoptic institution narratives, which use the Greek

Two of the most obvious and controversial changes in the new translation relate to the consecration of the precious blood. To begin the translation of Pro Multis is now rendered as "for many", whilst before it was translated "for all". This is closer to the synoptic institution narratives, which use the Greek