Today unicorns have a rather effeminate, placid reputation. One can see this in children's story books but also in the Harry Potter series, My Little Pony and a recent episode of Glee. This image is rather far removed from the ancient and medieval account of the fictional one-horned horse. It was seen as the fiercest and swiftest of all land creatures and could not be caught by any hunter. The only way to catch one was to put a virgin girl in its path. The unicorn, seeing the maiden, comes to her and puts its head in her lap and falls asleep. This fierce imagery is also used in the bible. In the Book of Numbers, God is described as having the strength of a Unicorn and the ability to tame the beast. The horns of the Unicorn are often used as a symbol of despair and terror in the Psalms and the Book of Job.

Today unicorns have a rather effeminate, placid reputation. One can see this in children's story books but also in the Harry Potter series, My Little Pony and a recent episode of Glee. This image is rather far removed from the ancient and medieval account of the fictional one-horned horse. It was seen as the fiercest and swiftest of all land creatures and could not be caught by any hunter. The only way to catch one was to put a virgin girl in its path. The unicorn, seeing the maiden, comes to her and puts its head in her lap and falls asleep. This fierce imagery is also used in the bible. In the Book of Numbers, God is described as having the strength of a Unicorn and the ability to tame the beast. The horns of the Unicorn are often used as a symbol of despair and terror in the Psalms and the Book of Job. Friday, September 30, 2011

Biblical Beasts: Unicorn

Today unicorns have a rather effeminate, placid reputation. One can see this in children's story books but also in the Harry Potter series, My Little Pony and a recent episode of Glee. This image is rather far removed from the ancient and medieval account of the fictional one-horned horse. It was seen as the fiercest and swiftest of all land creatures and could not be caught by any hunter. The only way to catch one was to put a virgin girl in its path. The unicorn, seeing the maiden, comes to her and puts its head in her lap and falls asleep. This fierce imagery is also used in the bible. In the Book of Numbers, God is described as having the strength of a Unicorn and the ability to tame the beast. The horns of the Unicorn are often used as a symbol of despair and terror in the Psalms and the Book of Job.

Today unicorns have a rather effeminate, placid reputation. One can see this in children's story books but also in the Harry Potter series, My Little Pony and a recent episode of Glee. This image is rather far removed from the ancient and medieval account of the fictional one-horned horse. It was seen as the fiercest and swiftest of all land creatures and could not be caught by any hunter. The only way to catch one was to put a virgin girl in its path. The unicorn, seeing the maiden, comes to her and puts its head in her lap and falls asleep. This fierce imagery is also used in the bible. In the Book of Numbers, God is described as having the strength of a Unicorn and the ability to tame the beast. The horns of the Unicorn are often used as a symbol of despair and terror in the Psalms and the Book of Job. Biblical Beasts: Snake

When one reads the story of the Fall in the book of Genesis, it is of no surprise that snakes have been associated with sin and the devil. In many ways the creature suits this anthropomorphism. For a mammal there is something sinister about it's cold-blooded reptilian ways and mannerisms but I also think that the snake, particularly captures the effects of sin of humanity. The medieval Aberdeen Bestiary declares that "All snakes are coiled and twisted, never straight. It is said that there are as many poisons, deaths and griefs as there are kinds of snakes." The fact that most snakes slither on the ground could also be said to display how through sin humanity has fallen in dignity from its God-given natural elevated and erect state. The snake's lack of true limbs also show how living in sin disables us; it makes us weaker; it limits our ability and opportunity.

When one reads the story of the Fall in the book of Genesis, it is of no surprise that snakes have been associated with sin and the devil. In many ways the creature suits this anthropomorphism. For a mammal there is something sinister about it's cold-blooded reptilian ways and mannerisms but I also think that the snake, particularly captures the effects of sin of humanity. The medieval Aberdeen Bestiary declares that "All snakes are coiled and twisted, never straight. It is said that there are as many poisons, deaths and griefs as there are kinds of snakes." The fact that most snakes slither on the ground could also be said to display how through sin humanity has fallen in dignity from its God-given natural elevated and erect state. The snake's lack of true limbs also show how living in sin disables us; it makes us weaker; it limits our ability and opportunity.Despite all this, the snake also offers a metaphor for solution. Snakes shed their skin by rubbing against rough surfaces, often rocks. We too can "shed our skins" of sins by going to the True Rock, that is Christ. Through him we are made new and freed from the tyranny of sin and death .

Wednesday, September 28, 2011

28th September: The Dominican Martyrs of Nagasaki

my beloved Father, let us so act that we may see one another in heaven for all eternity, fearing no separation here. Let us have no concern for this world, for it is our exile and separates us from God who is our total good. I say to my dearest sister: do not forget to commend me to God. To all my relatives and friends I send greetings. May the Lord keep you until you reach our heavenly homeland.

Thursday, September 22, 2011

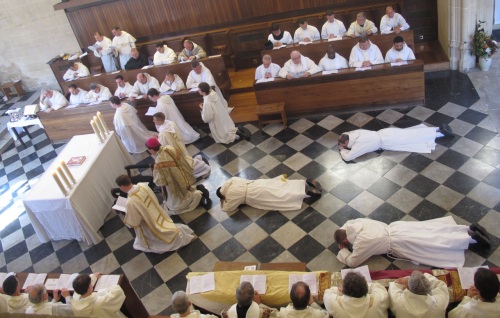

Ordinations at Blackfriars

Wednesday, September 21, 2011

Fruits of Study 7: Esse and Essentia

Monday, September 19, 2011

Simple and Solemn Professions 2011

Last weekend the Province of England has had much to celebrate. On the 10th of September, fr. Graham Hunt OP and fr. Gregory Pearson OP made solemn profession at Blackfriars, Oxford. In his homily the provincial, John Farrell OP, reflected on the fraternity of the Friars Preachers, which crosses both time and geography.

Last weekend the Province of England has had much to celebrate. On the 10th of September, fr. Graham Hunt OP and fr. Gregory Pearson OP made solemn profession at Blackfriars, Oxford. In his homily the provincial, John Farrell OP, reflected on the fraternity of the Friars Preachers, which crosses both time and geography.Biblical Beasts: Raven

The raven has a rather sinister reputation. Throughout history it has been used as a symbol of the macabre. One has to only think of Poe's poem The Raven, Marlowe's play The Jew of Malta and more recently the Omen trilogy. This association is not limited to the West. In the Koran it is the raven that teaches Cain how to bury his murdered brother Abel and amongst the Inuit people this scavenger is viewed as a 'trickster-god'.

Tuesday, September 13, 2011

Fruits of Study 6: Suffering and Love in St Catherine of Siena

Catherine of Siena (1347-80) was very practical and focused and on how to help people be saved and sanctified in the concrete situation of their lives. For her, suffering was a daily reality and one that can be crushing and an obstacle to a life of faith. She wanted people to see suffering in the light of God’s truth and goodness and then use it positively to produce a life of love and other virtues. As with other themes she relates this to the Crucified Christ, the centre of her thought.

Catherine of Siena (1347-80) was very practical and focused and on how to help people be saved and sanctified in the concrete situation of their lives. For her, suffering was a daily reality and one that can be crushing and an obstacle to a life of faith. She wanted people to see suffering in the light of God’s truth and goodness and then use it positively to produce a life of love and other virtues. As with other themes she relates this to the Crucified Christ, the centre of her thought. The cross of Christ demonstrates both God’s love and Christ’s virtue and very importantly it also allows us to be formed in virtue. According to Catherine, it builds us up on the foundation of Christ’s love, shown in him freely suffering for us. We love God in return for God’s love for us, and so are called to move from a state of selfishness to one of selflessness, that is to a life of real love. A life given over to such love will produce a life of virtues, love being the mother of virtues. And virtues grow as they are tested. Suffering, difficulty and adversity test them and so a human can grow in virtues. Thus patience, for instance, which Catherine sees as being at the heart of charity ‘is not proved except in suffering (D 5)’; ‘Justice is not lessened but proved by the injustices of others … Likewise your kindness and mildness are revealed through gentle patience in the presence of wrath … Steadfast courage is tested when you have to suffer much from people’s insults and slanders … (D 8).’ To love perfectly is to accept anything from God, any adversity, and to do so with a response of love, full of such other virtues as are required to live such love.

The cross of Christ demonstrates both God’s love and Christ’s virtue and very importantly it also allows us to be formed in virtue. According to Catherine, it builds us up on the foundation of Christ’s love, shown in him freely suffering for us. We love God in return for God’s love for us, and so are called to move from a state of selfishness to one of selflessness, that is to a life of real love. A life given over to such love will produce a life of virtues, love being the mother of virtues. And virtues grow as they are tested. Suffering, difficulty and adversity test them and so a human can grow in virtues. Thus patience, for instance, which Catherine sees as being at the heart of charity ‘is not proved except in suffering (D 5)’; ‘Justice is not lessened but proved by the injustices of others … Likewise your kindness and mildness are revealed through gentle patience in the presence of wrath … Steadfast courage is tested when you have to suffer much from people’s insults and slanders … (D 8).’ To love perfectly is to accept anything from God, any adversity, and to do so with a response of love, full of such other virtues as are required to live such love.Monday, September 12, 2011

22nd July

From this moment, something happened in me, and something happened in the soul of the Norwegian people. The first reaction came immediately: State leaders, especially the prime minister Jens Stoltenberg, our king Harald V, and the government stood together with the same message: This act of violence provokes fear and anxiety. We are not going to let our minds and our decisions be driven by this fear. This public signal found its echo among the people. Two days after the killings I was crossing Oslo city by bus. On a wall surrounding a Kindergarten there was a sign: "We must stick together". This is what the Norwegian people have done. We have stuck together, wept together, talked together. 200,000 people met in front of the city hall in Oslo on Sunday the 24th, everyone carrying flowers in their hands.

The open acceptance of our human reactions, and the embracing attitude of fellowship and love have marked Norwegian society and the media. All this is quite different from what has been the reaction to similar events in some other countries. The public debate has often been marked and driven by fear, defense, with restrictions and more intense supervision of the society as result. This may be justified and necessary. Still, there are important questions a society must ask itself: Fear and anxiety or fellowship and solidarity? I believe that our national leaders have managed to stop or at least limit the evil spinning wheel that always follows fear: Anxiety engenders anxiety, violence engenders violence. The open manifestation of a tolerance and peace as the foundation for the political and democratic future has been a true blessing for our nation, and stands as an example for all in time to come.

In an article written in The Telegraph one week after the killings (29th August), Anthony Browne claims that it is time for Norway to 'confront its racist demons (like GB has)', and he explains us that 'this tragedy marks the end of Norway’s innocence'. Yes, innocence is lost. But is this about racist demons? I do believe that it is about something worse. Finn Skårderud, a psychiatrist and well known Norwegian author says in an article in Dagbladet Magasinet on the 30th July that it is time to draw the attention to what’s going on in the lives of children. We see into their rooms and blindly trust the child when they assure us that everything is ok. Reality can sometimes be quite different. Here Skårderud touches a pathology engendered by our

After 22nd July everybody demand that the government take action to prevent such horrors happening again. But we also, each one of us, are challenged. We all carry a responsibility to fight these pathological patterns. By engagement in our local society, and by confronting hateful attitudes, opinions and actions, we may take responsibility for the society we live in. If we don’t, we ourselves risk becoming responsible for the violence that surrounds us. We may not be able to save the world, but we are called to do what we can. Only through real relations can we create the humanism necessary for our common wellbeing. If we search for demons as Browne tends to do, we may easily spot the diabolic side of internet in this disaster. Breivik entered into a web of people he thought where his allies. He lived in false fellowship with catastrophic outcome. One of his inspiration sources, 'Fjordman', and many with him, will have to consider how their own statements have become part of the tragedy of the 22nd July.

One month after the tragedy another event took place that may be seen as reverse image of what happened in Norway. I'm thinking of the World Youth Days in Madrid. On an airport, almost 2 million young people met to pray and praise. This Catholic meeting based on love, respect and peace shows us that true fellowship is possible, and that it can reach all around the world. At the final Mass a group of about 200 Norwegians participated with black bands tied to their flags in solidarity with the memorial ceremony taking place in Norway the same day. It was a breathtaking celebration, showing the world how Catholics from all over the world commit themselves to the same God, carrying to the world a gospel that holds love, peace and truth as the foundation for our existence.

Flowers still fill the Church gates and the streets of Oslo; roses are often laid down with tears. The Norwegian people are still mourning. In a small, peaceful country, love has been challenged. And with it presents a challenge for the nation, and for each one of us. May God give us the strength to stand up for true human values in our society.

Sunday, September 11, 2011

Fruits of Study 5: Creation Ex Nihilo

Creation would then seem to be the pivotal issue. However, we would be wrong to think that this debate is somehow new: we just have very short or very selective memories. When Thomas Aquinas was penning his Summa in the thirteenth century the same controversy was very much apparent in the new universities. Indeed, a scientific revolution was under-way across Western Europe as the works of the ancient Greek natural philosophers and mathematicians became available in Latin for the first time. Specifically, many held that there must be a fundamental incompatibility between the claim of the Greek naturalists that something cannot come from nothing, and the Christian teaching of creatio ex nihilo, creation from nothing.

Aquinas couldn't conceive that there could be an incompatibility between the two positions – what we now may call science and religion. Christian doctrine maintains that God is the author of all Truth; the aim of rigorous scientific investigation is to find the Truth. Why should one side fear the other? In fact, are we not on the same side if we believe in Truth at all? Well, it wasn't to be that clear cut then and it doesn't seem that much has changed. In straightforward terms, the problem would appear to be complete confusion by what we mean by the nature of creation and natural change.

Thomas, when speaking of creation, is not pondering how one thing came to be from another thing but what is common to all things in the universe, namely existence. But what is the cause of all existence? Is it a cause in the sense of a natural change or of some kind or an ultimate bringing into being of something from no antecedent state whatsoever by Divine Agency? Here lies the fundamental conflict; there is simply a major misunderstanding in the use of the term creation. By seeking to ground it solely in the realm of the natural sciences and being unwilling to admit it has a place in metaphysics and theology we will continue to grope blindly in the dark.

The Greeks were in fact correct, nothing comes from nothing, if we understand rightly that 'comes from' implies a change. Change from one natural state to another requires some pre-existant material reality. A possibility for change must lie in something, there must be potentiality. Creation on the other hand differs as it is the radical causing of the whole existence of whatever there is in existence. We can see the difference if we look at how being the cause of something's whole existence must in fact be different from causing a change in something that exists. In other words, we are not talking of God taking a bit of this and a bit of that and putting a universe together. Creation then, is not a change in matter but a cause; God produces existence absolutely ex nihilo. This act of creation may also be seen as one of conservation, that is God did not simply create in one distant moment and exit the next. Creation is a continual action by which he gives existence as he upholds the world in being.

Without God, the Cause, there can be no effect. The ability that creatures have to act only comes by virtue of their existence. So yes we can make some things, change some things and observe change in other existing realities but we cannot create. Creation accounts for the very existence of things not for changes in things. Only God can create, he is like the ultimate power source that if it were to cease then out would go the lights – only there would be no lights!

Biblical Beasts: Tortoise

The tortoise gets a mention (in some translations) in Leviticus 11:29-30. It appears on a list of unclean animals named as follows in the Revised Standard Version: 'these are unclean to you among the swarming things that swarm upon the earth: the weasel, the mouse, the great lizard according to its kind, the gecko, the land crocodile, the lizard, the sand lizard, and the chameleon'. The first 'great lizard' is sometimes translated as the 'tortoise after its kind'. They are the small Leviathans, we might say, lizards and hard shelled creatures that creep along the earth. This family of creatures is fascinating and can be unsettling: there are some beautiful lizards and some startling ones, some tiny tortoises and some enormous ones.

The tortoise gets a mention (in some translations) in Leviticus 11:29-30. It appears on a list of unclean animals named as follows in the Revised Standard Version: 'these are unclean to you among the swarming things that swarm upon the earth: the weasel, the mouse, the great lizard according to its kind, the gecko, the land crocodile, the lizard, the sand lizard, and the chameleon'. The first 'great lizard' is sometimes translated as the 'tortoise after its kind'. They are the small Leviathans, we might say, lizards and hard shelled creatures that creep along the earth. This family of creatures is fascinating and can be unsettling: there are some beautiful lizards and some startling ones, some tiny tortoises and some enormous ones.Saturday, September 10, 2011

Friday, September 9, 2011

Quail

We find two references to Quail in the Old Testament: first, in Exodus chapter 15, and then again in Numbers chapter 11. In both instances God provides the people of Israel with meat in the form of these birds in response to their grumblings and complaints about the hardships of the desert. Yet the two accounts are subtly and interestingly different.

In Numbers Chapter 11, however, the context is slightly different. Here the people have already received the gift of the Manna, they have already received the bread from heaven, the food for the journey - and they are sick of it. They are bored of this food and once more long for the variety of their diet in Egypt. The sacrifices of freedom are too high. The consolations of slavery much too alluring. Once again God provides responds to the complaints of his people by providing meat in the form of Quail, but this time he promises Israel that they will grow tired of this meat too. He tells Israel: ' You will eat it [meat]....for a month until it comes out of your nostrils and sickens you' (Numbers 11: 20).

Here the Quail represent all the sensual, intellectual and emotional consolations that we turn to in order to avoid the cross of Christ, in order to avoid the sacrifices that love of God and love of neighbour demand. Eventually these consolations become revolting and we must search for another 'fix'. As Augustine puts it, our hearts are restless until they rest in God. This is the hard lesson that the Israelites learnt by enduring the privations of the desert for forty years. It is a lesson that we too must learn if we are to fully embrace our freedom as children of God and finally dispel all thoughts of returning to the slavery of sin.

Tuesday, September 6, 2011

Fruits of Study 4: The Development of Doctrine

Rather than being a clear and distinct idea that we possess and comprehend, then, the Gospel is more like an active principle within us that comes to define who we are and how we live. As we go through life, the Gospel, this 'active principle' that organises our lives, is continually re-applied and re-expressed in the new contexts and situations that we face. In this process of re-application of the Gospel in the lives of Christians and Christian communities, the doctrinal and liturgical tradition of the Church is deepened as new perspectives on the Incarnation of Christ are uncovered.

For Newman, then, doctrinal and liturgical development is not a sign of contamination or decay, it is a sign of life. We do not live our Christian life in a vacuum. We live our Christian lives in a world that is continually changing. Fidelity to the unchanging content of the Gospel, then, means developing and changing ways of expressing and articulating that same Gospel. As Newman himself puts it: 'To live is to change and to be perfect is to have changed often'. To put this same point another way, Newman is offering us a quasi-organic understanding of doctrinal and liturgical development. The Catholic Church is the tree that grew from the mustard seed. Whilst it may now look very different to its first manifestation, there is a direct correspondence between its primitive state and its contemporary state. The Protestant sects and Chapel congregations of Newman's day, in contrast, whilst they may have superficially looked more like the early Church than nineteenth century Catholicism, were in fact fundamentally as different from the Church of the apostolic age as a mustard seed is from an acorn.

Sunday, September 4, 2011

Biblical Beasts: Pig

The other famous pig incident in the New Testament may have some connection with this. It concerns the exorcism of a man and the casting of his demons into a herd of 2000 pigs that rush into the sea and are drowned (Mk 5 and parallels in Mt 8 and Lk 8). The devils recognise the holiness of Jesus – calling him Son of the Most High – and name themselves as Legion, a term specific to Roman military use, and meaning a fighting group of 6000 men. Jesus will not tolerate their presence but they hope to stay in the area and ask that he will allow them to go into the unclean pigs. But this does not work out and the demons end up in the sea, a realm under God’s authority, and something over which Jesus has specifically exercised his authority in the previous chapter.

The other famous pig incident in the New Testament may have some connection with this. It concerns the exorcism of a man and the casting of his demons into a herd of 2000 pigs that rush into the sea and are drowned (Mk 5 and parallels in Mt 8 and Lk 8). The devils recognise the holiness of Jesus – calling him Son of the Most High – and name themselves as Legion, a term specific to Roman military use, and meaning a fighting group of 6000 men. Jesus will not tolerate their presence but they hope to stay in the area and ask that he will allow them to go into the unclean pigs. But this does not work out and the demons end up in the sea, a realm under God’s authority, and something over which Jesus has specifically exercised his authority in the previous chapter.Saturday, September 3, 2011

The Angelicum

Friday, September 2, 2011

Fruits of Study 3: Re-enchanting Education

Taking as his starting point Benedict XVI’s appeal for a liturgical understanding of human existence, Caldecott shows how the rationalism that has reduced western education to something purely utilitarian, will be overcome through a fresh appreciation of the transcendentals of truth and goodness, but only where the neglected transcendental, beauty, is allowed to work its influence. The perception of form is fundamental if the elimination of meaning is to be reversed.

Taking as his starting point Benedict XVI’s appeal for a liturgical understanding of human existence, Caldecott shows how the rationalism that has reduced western education to something purely utilitarian, will be overcome through a fresh appreciation of the transcendentals of truth and goodness, but only where the neglected transcendental, beauty, is allowed to work its influence. The perception of form is fundamental if the elimination of meaning is to be reversed.