Henri Matisse's 'The Way of the Cross' is in the Rosary Chapel, Vence, France. The chapel was solemnly consecrated on 25 June 1951. It belongs to the Dominican sisters who run a home of convalescence in Vence which is in the hills high above the city of Nice. The architect and decorator of the chapel was Henri Matisse. On the day of its consecration a crowd consisting of religious, clergy, and a great number of journalists was waiting impatiently outside the door. Finally, the local bishop opened the doors, and the crowd entered. The ones who entered were amazed by the light flowing in through the stained glass windows in yellow, green, and blue. On the right hand side, a beautiful painting covering the whole wall showed Mary and the Child surrounded by clouds. It was painted with black ink on white tiles, and the colours from the windows added life to the image. At the far end stood the altar in sand stone, and behind this, another stained glass window called “The Tree of Life”. To the left they could admire the choir for the sisters, and on the right, another enormous painting, this one of Saint Dominic. Everything was made by Matisse, not only the paintings and the windows, but also the altar, the choir, and the crucifix. Even the volume and shape of the chapel were designed by the artist, nothing had escaped his hand, and all who entered the place were touched by its beauty. Until they turned and saw the Way of the Cross!

One could hear the clergy mumbling the word blasphemy, at first quietly and later all over the front pages of the newspapers. The press speculated and wondered if Matisse had run out of time, and was forced to scribble down the Way of the Cross at the last minute. Why would Matisse add something so ugly in such a beautiful place

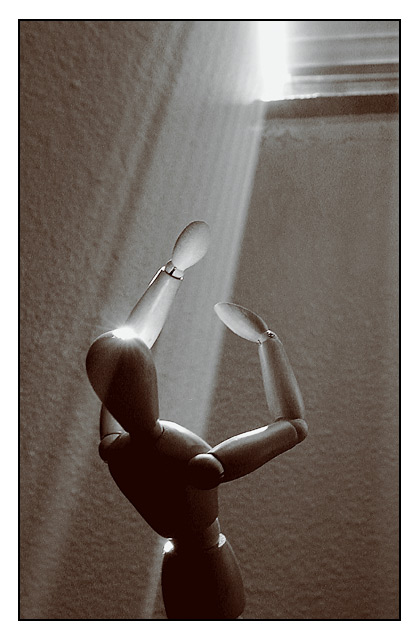

Matisse had not run out of time. The Way of the Cross had been worked through, over and over again. Each scene had been sketched in several versions. Matisse was studying, struggling, fighting with his own drafts to find the right expression. How could he possibly visualize Christ’s suffering in a place that otherwise reflected sublime beauty? When the journalists asked him about the expression of the Way of the Cross, Matisse answered firmly: “I have not painted beauty. I have painted the Truth. The truth of the Passion is not, and has never been beautiful!” Matisse had not been painting. He had lived through the passion himself. It was not the result of eccentric spontaneity that one could see on the wall, but a meditation on the passion that lasted for years. It took Henri Matisse four years to complete the chapel, and when he finished he said: “This chapel is the sum of my whole life as an artist.”

Henri Matisse never confessed his faith, and remained at a distance from the Church. But in quiet mornings in the following few years before he died, the sisters would sometimes see him sitting in the back of the chapel, just under the Way of the Cross, silently weeping as the sisters sung their Benedictus ...