Tuesday, August 31, 2010

Papal Visit I: The Significance of Cardinal Newman

Monday, August 30, 2010

General Chapter 2010

Today in Rome, friars from across the globe will begin to assemble for the two-hundredth and ninetieth General Chapter of the Order of Preachers. The General Chapter is the supreme governing authority in the Dominican Order. It is an assembly of friars, representing all the Provinces of the Order, coming together to discuss and define matters pertaining to the good of the entire Order. One of the most important tasks facing the 130 delegates at this Chapter is to elect a Master of the Order.

The General Chapter has its own website which is full of information and which will be updated with news, as the Chapter progresses. Please keep the Order and especially the members of the Chapter, in your prayers at this time.

Blackfriars Oxford featured on BBC's 'Faith Place'

fr Lawrence Lew OP takes to the airwaves again! This time he was interviewed by BBC Radio Oxford for Faith Place, a segment presented by the Rev Hedley Feast for their Sunday morning programme. The first half of the 20 minute interview, which was recorded in Blackfriars Priory church, was aired yesterday, Sunday 29 August. To listen to the programme, click here, and fast forward to the 1hr 9min mark. The second and final half of the interview will be aired next Sunday, 5 September.

Thursday, August 26, 2010

A - Z of the Mass: Prayers

Christian prayer is a remembrance of God, a memorial, and the Eucharist reveals the meaning of Christian prayer as a memorial of Christ's sacrifice on the cross. Christ, our great High Priest and our Intercessor bears in Himself before the Father all the prayers of the Church. Our prayer ascends to God with those of the angels and the saints, and the Son of God, in virtue of His sacrifice, grants our prayer in the unity of the Father and the Spirit. So whilst we should still make time for private prayer, we should not forget that it is Christ revealed to us in the Eucharist, who allows all our prayer, whether in private or public, to be a time when our hearts and minds are truly raised to God.

Christian prayer is a remembrance of God, a memorial, and the Eucharist reveals the meaning of Christian prayer as a memorial of Christ's sacrifice on the cross. Christ, our great High Priest and our Intercessor bears in Himself before the Father all the prayers of the Church. Our prayer ascends to God with those of the angels and the saints, and the Son of God, in virtue of His sacrifice, grants our prayer in the unity of the Father and the Spirit. So whilst we should still make time for private prayer, we should not forget that it is Christ revealed to us in the Eucharist, who allows all our prayer, whether in private or public, to be a time when our hearts and minds are truly raised to God.Sunday, August 22, 2010

A - Z of the Mass: Offerings

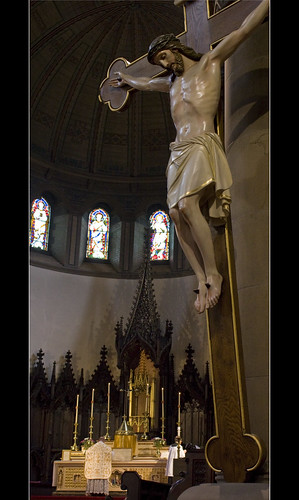

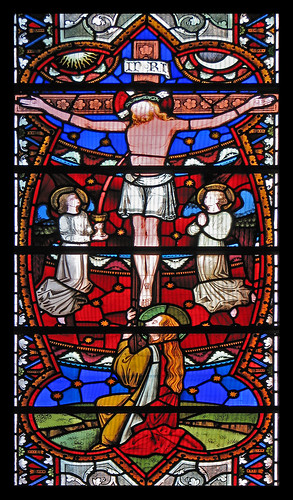

At the centre of the Eucharistic action is the idea of offering. As the Catechism says: "The Eucharist is the memorial of Christ's Passover, the making present and the sacramental offering of his unique sacrifice, in the liturgy of the Church which is his Body" (§1362). An offering is something freely given to another, in this case God, and it has a sacrificial element which is perfected if it is given out of love. St Thomas cites St Augustine saying that "'Christ offered Himself up for us in the Passion': and this voluntary enduring of the Passion was most acceptable to God, as coming from charity" (ST III 48,3). The Mass is the sacramental sign of the one Sacrifice of Christ's Passion, such that Christ's perfect offering on the Cross is made present in the perfect offering of the Mass. Again, as the Catechism (quoting the Council of Trent) says: "The victim is one and the same: the same now offers through the ministry of priests, who then offered himself on the cross; only the manner of offering is different" (CCC §1367). So, the ordained priest, acting in the person of Christ, offers the Body and Blood of Christ, the "acceptable sacrifice", to the Father.

At the centre of the Eucharistic action is the idea of offering. As the Catechism says: "The Eucharist is the memorial of Christ's Passover, the making present and the sacramental offering of his unique sacrifice, in the liturgy of the Church which is his Body" (§1362). An offering is something freely given to another, in this case God, and it has a sacrificial element which is perfected if it is given out of love. St Thomas cites St Augustine saying that "'Christ offered Himself up for us in the Passion': and this voluntary enduring of the Passion was most acceptable to God, as coming from charity" (ST III 48,3). The Mass is the sacramental sign of the one Sacrifice of Christ's Passion, such that Christ's perfect offering on the Cross is made present in the perfect offering of the Mass. Again, as the Catechism (quoting the Council of Trent) says: "The victim is one and the same: the same now offers through the ministry of priests, who then offered himself on the cross; only the manner of offering is different" (CCC §1367). So, the ordained priest, acting in the person of Christ, offers the Body and Blood of Christ, the "acceptable sacrifice", to the Father. Moreover, as Pope Benedict XVI said: "In this way we also bring to the altar all the pain and suffering of the world, in the certainty that everything has value in God's eyes... [This gesture] enables us to appreciate how God invites man to participate in bringing to fulfilment his handiwork, and in so doing, gives human labour its authentic meaning, since, through the celebration of the Eucharist, it is united to the redemptive sacrifice of Christ" (Sacramentum caritatis, §47).

Moreover, as Pope Benedict XVI said: "In this way we also bring to the altar all the pain and suffering of the world, in the certainty that everything has value in God's eyes... [This gesture] enables us to appreciate how God invites man to participate in bringing to fulfilment his handiwork, and in so doing, gives human labour its authentic meaning, since, through the celebration of the Eucharist, it is united to the redemptive sacrifice of Christ" (Sacramentum caritatis, §47).Thirdly, in the Mass the Body of Christ, meaning the entire Church, is offered to the Holy Trinity. So, the Catechism says: "The Church which is the Body of Christ participates in the offering of her Head. With him, she herself is offered whole and entire. She unites herself to his intercession with the Father for all men" (CCC §1368).

Wednesday, August 18, 2010

A-Z of the Mass: 'N'

Lord, remember your Church through the world;

Lord, remember your Church through the world;make us grow in love,

together with N our Pope,

N our Bishop, and all the clergy.

Remember, Lord, your people, especially those for whom we now pray, N. and N.

The other is a naming of the dead for whom the community wishes particularly to pray:

Remember, Lord, those who have died and have gone before us marked with the sign of faith, especially those for whom we now pray, N. and N.

The first Eucharistic Prayer gives us a list of saints and martyrs who are to be mentioned by name. These are the most important saints of the early Church: Mary, Joseph, John the Baptist, Stephen, the apostles, and other confessors and martyrs, many of them Roman saints. The third Eucharistic Prayer gives the option of naming a saint, 'Saint N', the saint of the day or a patron saint. It has become customary also for the second and fourth Eucharistic Prayers to include the naming of a particular saint (or even saints).

The first Eucharistic Prayer gives us a list of saints and martyrs who are to be mentioned by name. These are the most important saints of the early Church: Mary, Joseph, John the Baptist, Stephen, the apostles, and other confessors and martyrs, many of them Roman saints. The third Eucharistic Prayer gives the option of naming a saint, 'Saint N', the saint of the day or a patron saint. It has become customary also for the second and fourth Eucharistic Prayers to include the naming of a particular saint (or even saints).Sunday, August 15, 2010

A-Z of the Mass: Memorial

Societies, clubs and associations up and down the country exist to 'remember' the lives and works of particularly worthy individuals. The Church is fundamentally different from such institutions. We do not come to Mass simply to learn about Christ and try to imitate him, as we might study the works of Aristotle for instance, or Marx. We come to Mass to share in the life of the living God. We come to Mass to renew our communion with Christ and each other.

Societies, clubs and associations up and down the country exist to 'remember' the lives and works of particularly worthy individuals. The Church is fundamentally different from such institutions. We do not come to Mass simply to learn about Christ and try to imitate him, as we might study the works of Aristotle for instance, or Marx. We come to Mass to share in the life of the living God. We come to Mass to renew our communion with Christ and each other.Saturday, August 14, 2010

Mother of Redeemed Humanity

Elizabeth calls Mary “the mother of my Lord”, and her use of the word ‘Lord’ is significant because it refers to God, the Lord whom Mary praises in her ‘Magnificat’. And so, every time we pray the ‘Hail Mary’, we repeat the words of both Gabriel and Elizabeth, and we echo Elizabeth’s greeting when we call Mary “Mother of God”. But it’s not because Mary is Mother of God that we celebrate today’s feast. No, we celebrate Mary’s Assumption, when “the ever Virgin Mary, having completed the course of her earthly life, was assumed body and soul into heavenly glory” because Mary is ‘Mother of Man’, the Mother of Humanity.

Elizabeth calls Mary “the mother of my Lord”, and her use of the word ‘Lord’ is significant because it refers to God, the Lord whom Mary praises in her ‘Magnificat’. And so, every time we pray the ‘Hail Mary’, we repeat the words of both Gabriel and Elizabeth, and we echo Elizabeth’s greeting when we call Mary “Mother of God”. But it’s not because Mary is Mother of God that we celebrate today’s feast. No, we celebrate Mary’s Assumption, when “the ever Virgin Mary, having completed the course of her earthly life, was assumed body and soul into heavenly glory” because Mary is ‘Mother of Man’, the Mother of Humanity. As Mother of the Church, then, Mary is our Mother, and she is the first in the Church to benefit from Christ’s promises. She is the first to receive the grace of divine adoption, so in today's psalm she is called ‘daughter’. And today we celebrate that she is the first to rise body and soul into heaven to be with God. So, the eternal life that was promised to her by her adoption as a child of God, a sharer in the divine life, was fulfilled at the end of her earthly life. So too with us … When our earthly life is ended, we hope that the promise given to us in baptism will be fulfilled by God’s grace, so that we too will be assumed body and soul into heavenly glory!

As Mother of the Church, then, Mary is our Mother, and she is the first in the Church to benefit from Christ’s promises. She is the first to receive the grace of divine adoption, so in today's psalm she is called ‘daughter’. And today we celebrate that she is the first to rise body and soul into heaven to be with God. So, the eternal life that was promised to her by her adoption as a child of God, a sharer in the divine life, was fulfilled at the end of her earthly life. So too with us … When our earthly life is ended, we hope that the promise given to us in baptism will be fulfilled by God’s grace, so that we too will be assumed body and soul into heavenly glory!Wednesday, August 11, 2010

A to Z of the Mass - Language

Clearly, language plays an important part in the celebration of the Eucharist: after all, we say that it is the words spoken by the priest (its ‘form’) over the bread and wine (its 'matter') that effect the sacrament in which Christ is really present under the appearances of that bread and wine. But how do we dare claim such power for these words, elements of human language? And why these words in particular? And what about the rest of the liturgical rite of the Mass, also composed of various texts? After all, is God not beyond language, limited as it is by the boundaries of the human mind? How can any prayer we say, with any form of words, be worthy of any response from God, let alone the gift of the Body and Blood of Christ which He gives us in the Eucharist?

Clearly, language plays an important part in the celebration of the Eucharist: after all, we say that it is the words spoken by the priest (its ‘form’) over the bread and wine (its 'matter') that effect the sacrament in which Christ is really present under the appearances of that bread and wine. But how do we dare claim such power for these words, elements of human language? And why these words in particular? And what about the rest of the liturgical rite of the Mass, also composed of various texts? After all, is God not beyond language, limited as it is by the boundaries of the human mind? How can any prayer we say, with any form of words, be worthy of any response from God, let alone the gift of the Body and Blood of Christ which He gives us in the Eucharist?In brief, yes, God is beyond our language. We cannot praise or thank him as we ought. It is because of this gap, however, this distance from Him, that He sent his Son into the world to become a human being like us: Jesus calls us to unite us to himself, the Word made Flesh, and by his Spirit to come to participate in the eternal love which the Son speaks to the Father and the Father to the Son.

Thus, as our humanity is raised up to God through the Incarnation, so our human language is raised up, and made capable in the sacraments of pointing to something beyond itself, bringing about something which it is not fully able to describe. At the consecration of the Mass it is Jesus who speaks the words of institution through the priest as his instrument: they are truly his words, given to the Church at the Last Supper and handed down in the gospels and the tradition of the Church.

The various other texts which constitute the different rites of Mass have also developed within the tradition of the Church. By using these texts, ordered and selected according to a set pattern, we remember and signify that every celebration of the Eucharist is an action of the whole Church, not of some individual or special group: it is language which makes human beings capable of society, and through a particular use of language that something can be said on behalf of a society as a whole.

Our language, then, is not capable of speaking definitively about God, or of expressing the praise and thanks which is his due, but through the Incarnation, God elevates our speech so that, by the power of the Word made flesh, Christ’s Body and Blood can be made really present, under the appearance of bread and wine, by the speaking of words. These words form part of a rite given to us by the Church, to whom Jesus gave the command to celebrate the Eucharist.

Sunday, August 8, 2010

A-Z of the Mass: Kneeling

We kneel during the Eucharistic prayer as this is the most important part of the Mass; it is when Our Lord becomes present in the Blessed Sacrament. Many would argue that this is an innovation of the medieval ages, when people would adopt similar postures in the presence of their social superiors. This might be the case, but if one is willing to kneel before a king is it not acceptable to kneel before the King of kings?

We kneel during the Eucharistic prayer as this is the most important part of the Mass; it is when Our Lord becomes present in the Blessed Sacrament. Many would argue that this is an innovation of the medieval ages, when people would adopt similar postures in the presence of their social superiors. This might be the case, but if one is willing to kneel before a king is it not acceptable to kneel before the King of kings?Kneeling is also a posture of intimacy. When Christ was suffering the agony in the garden he shared his intimate prayer with the Father on his knees.And it is also a gesture of trust. We are vulnerable and at a disadvantage physically but we can trust in God, and the Blessed Sacrament is the embodiment of that trust.

The Catholic Encyclopedia includes a very interesting article on kneeling. You can read it on the New Advent website, here.

Saturday, August 7, 2010

St Dominic's Day in Newcastle

Readings: Isaiah 52: 7-10; Psalm 96; 2 Timothy 4:1-8; Luke 10:1-9

On the very day that Saint Dominic died - 6 August 1221 - the Dominican friars, in their distinctive black and white habits, first stepped onto the shores of England. Eighteen years later, in 1239, when they had come to maturity in this land, they arrived in Newcastle. And so the distinctive colours of black and white were first brought to the streets of this great city by the Black Friars, and those colours are still so prominent in Newcastle, thanks (it is said) to Dominican influence!

On the very day that Saint Dominic died - 6 August 1221 - the Dominican friars, in their distinctive black and white habits, first stepped onto the shores of England. Eighteen years later, in 1239, when they had come to maturity in this land, they arrived in Newcastle. And so the distinctive colours of black and white were first brought to the streets of this great city by the Black Friars, and those colours are still so prominent in Newcastle, thanks (it is said) to Dominican influence! Firstly, there’s urgency because there’s a real hunger, and a great need in our world, and yes, in this very city, this parish, today. And when someone is in desperate need, it would be heartless to just dilly-dally. St Dominic saw in his time that people were being misled by all sorts of false ideas that de-humanized them, and denigrated the goodness and holiness of God’s creation. He experienced for himself the real need for well-trained, sound teachers of the Truth, and he saw how desperate people were for the Gospel of Jesus Christ. The Good News, that should be heard, and preached, and experienced by the world as Good News! And I’m sure you’ll agree that there is still the same need today. This is not because the first Black Friars were unsuccessful, but because each age has different challenges, temptations and difficulties, and each generation is called to respond to the needs of the day, and to preach the Word of God in that situation.

Firstly, there’s urgency because there’s a real hunger, and a great need in our world, and yes, in this very city, this parish, today. And when someone is in desperate need, it would be heartless to just dilly-dally. St Dominic saw in his time that people were being misled by all sorts of false ideas that de-humanized them, and denigrated the goodness and holiness of God’s creation. He experienced for himself the real need for well-trained, sound teachers of the Truth, and he saw how desperate people were for the Gospel of Jesus Christ. The Good News, that should be heard, and preached, and experienced by the world as Good News! And I’m sure you’ll agree that there is still the same need today. This is not because the first Black Friars were unsuccessful, but because each age has different challenges, temptations and difficulties, and each generation is called to respond to the needs of the day, and to preach the Word of God in that situation. This excitement and joy, and an awareness of the urgency of the mission is what caused St Dominic to send out his brothers even into hostile territories, “like lambs among wolves”. So they came even here to the limits of Hadrian’s Wall, and then beyond. And these men first walked the streets of Newcastle in their black and white colours with a buzz of excitement, urgency, and resounding shouts of joy. They shouted with joy that God had comforted and redeemed his people in Christ, and that because of Jesus, the kingdom of God, God’s salvation, had come to humanity.

This excitement and joy, and an awareness of the urgency of the mission is what caused St Dominic to send out his brothers even into hostile territories, “like lambs among wolves”. So they came even here to the limits of Hadrian’s Wall, and then beyond. And these men first walked the streets of Newcastle in their black and white colours with a buzz of excitement, urgency, and resounding shouts of joy. They shouted with joy that God had comforted and redeemed his people in Christ, and that because of Jesus, the kingdom of God, God’s salvation, had come to humanity.Wednesday, August 4, 2010

A-Z of the Mass - Jewish Synagogue Worship

Jewish synagogue worship can be seen to arise in the wake of the Babylonian destruction of the first Temple constructed by Solomon. Though a second and grander construction was built by Herod in the first century, the legacy of the exile remained and the organised worship that had flourished during this period, synagogue worship, became a permanent part of Jewish religious life. Even after the return to Israel this form of ritual worship was enshrined for the simple reason that all could not reach the Temple. The synagogue became the local house of worship and over time many aspects of Jewish liturgical ritual developed and became formalised. Much was naturally modeled on Temple worship, the buildings faced east towards Jerusalem and each contained a Torah Ark. In this the scrolls of the Torah were kept – this was to be reminiscent of the Ark of the Covenant where the Ten Commandments were held in the Holy of Holies, the inner sanctuary of the Tabernacle, in the First Temple. Each synagogue also contained a bimah, a raised platform from which the scriptures were read by those competent to do so and from which teaching and instruction were given. Above all, synagogue worship, in contrast to the sacrificial forms of Temple worship, was characterized by the recitation of prayer, the reading of scripture, and the chanting of the Psalms.

Jewish synagogue worship can be seen to arise in the wake of the Babylonian destruction of the first Temple constructed by Solomon. Though a second and grander construction was built by Herod in the first century, the legacy of the exile remained and the organised worship that had flourished during this period, synagogue worship, became a permanent part of Jewish religious life. Even after the return to Israel this form of ritual worship was enshrined for the simple reason that all could not reach the Temple. The synagogue became the local house of worship and over time many aspects of Jewish liturgical ritual developed and became formalised. Much was naturally modeled on Temple worship, the buildings faced east towards Jerusalem and each contained a Torah Ark. In this the scrolls of the Torah were kept – this was to be reminiscent of the Ark of the Covenant where the Ten Commandments were held in the Holy of Holies, the inner sanctuary of the Tabernacle, in the First Temple. Each synagogue also contained a bimah, a raised platform from which the scriptures were read by those competent to do so and from which teaching and instruction were given. Above all, synagogue worship, in contrast to the sacrificial forms of Temple worship, was characterized by the recitation of prayer, the reading of scripture, and the chanting of the Psalms. As with worship in the Catholic Church, synagogue customs and traditions varied from place to place though the central tenets and core beliefs remained the same. The Diaspora was at the heart of this variety which ultimately gave rise to the Sephardic and Ashkenazi forms of Judaism. After the destruction of the Second Temple by the Romans, the synagogue, with its didactic rather than sacrificial emphasis, became the central forum of all Jewish worship. Today we can see much of our Christian heritage reflected in the forms of Jewish worship and we hold much in common such as our reverence for scripture as the revealed Word of God. Our differences remain clear but it is important to reflect upon what we have inherited in order to better understand the true significance of that heritage. How else are we truly to understand Christ as the fulfilment of the Old Law, the Mass as a true sacrifice, and the inexhaustible richness of the Eucharist as the very ‘source and summit’ of the Christian life?

As with worship in the Catholic Church, synagogue customs and traditions varied from place to place though the central tenets and core beliefs remained the same. The Diaspora was at the heart of this variety which ultimately gave rise to the Sephardic and Ashkenazi forms of Judaism. After the destruction of the Second Temple by the Romans, the synagogue, with its didactic rather than sacrificial emphasis, became the central forum of all Jewish worship. Today we can see much of our Christian heritage reflected in the forms of Jewish worship and we hold much in common such as our reverence for scripture as the revealed Word of God. Our differences remain clear but it is important to reflect upon what we have inherited in order to better understand the true significance of that heritage. How else are we truly to understand Christ as the fulfilment of the Old Law, the Mass as a true sacrifice, and the inexhaustible richness of the Eucharist as the very ‘source and summit’ of the Christian life?Sunday, August 1, 2010

A-Z of the Mass: Incense